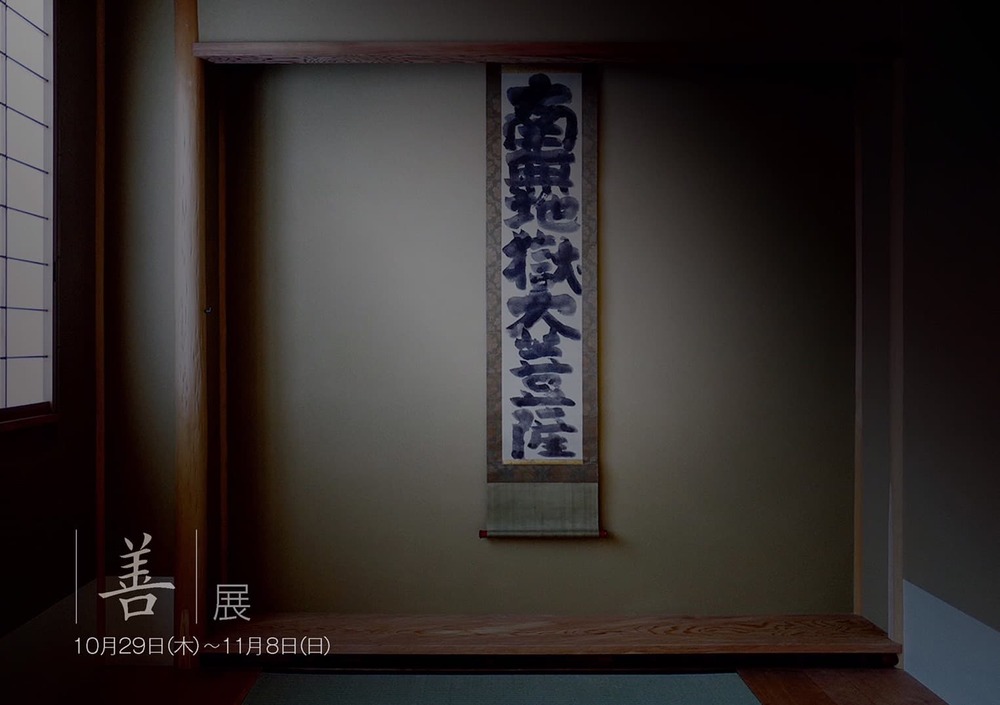

Goodness

2020.10.29-2020.11.08

We thought that hanging scrolls might have some use now when people spend more time at home thinking about things due to Covid-19, so we created an online exhibition webpage.

For this exhibition, we chose artworks with the theme “goodness”.

We believe our predecessors’ works will give us the opportunity to think about things as we re-examine ourselves and society.

We hope that by thinking about the historical background and content of these works slowly, they will provide hints to re-examine the present.

May this exhibition help you in looking at yourself in a new light.

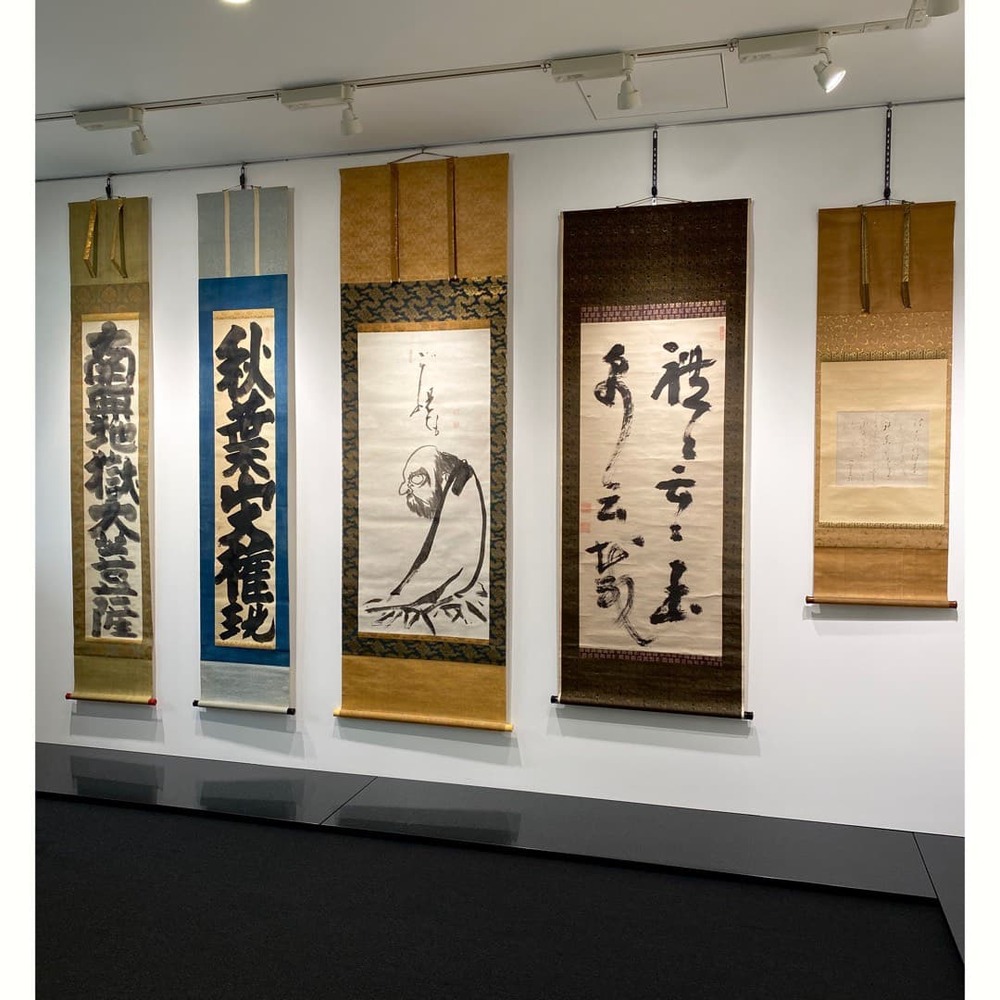

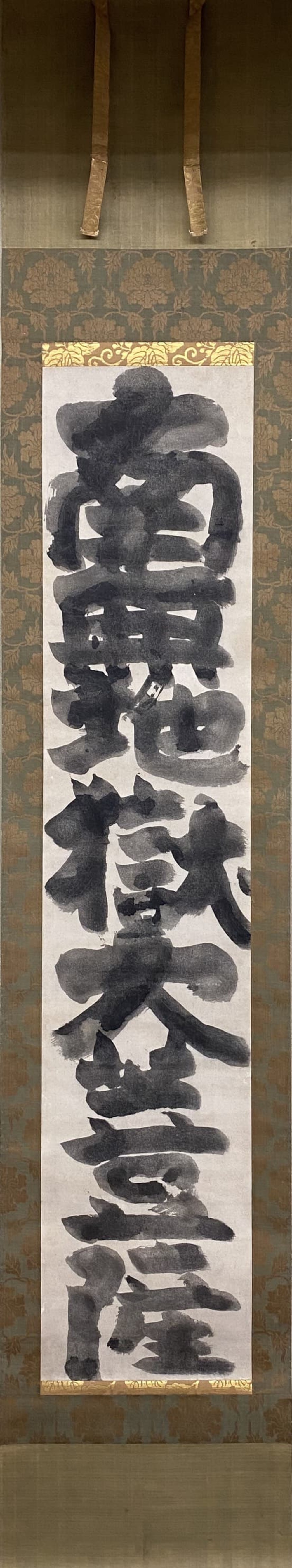

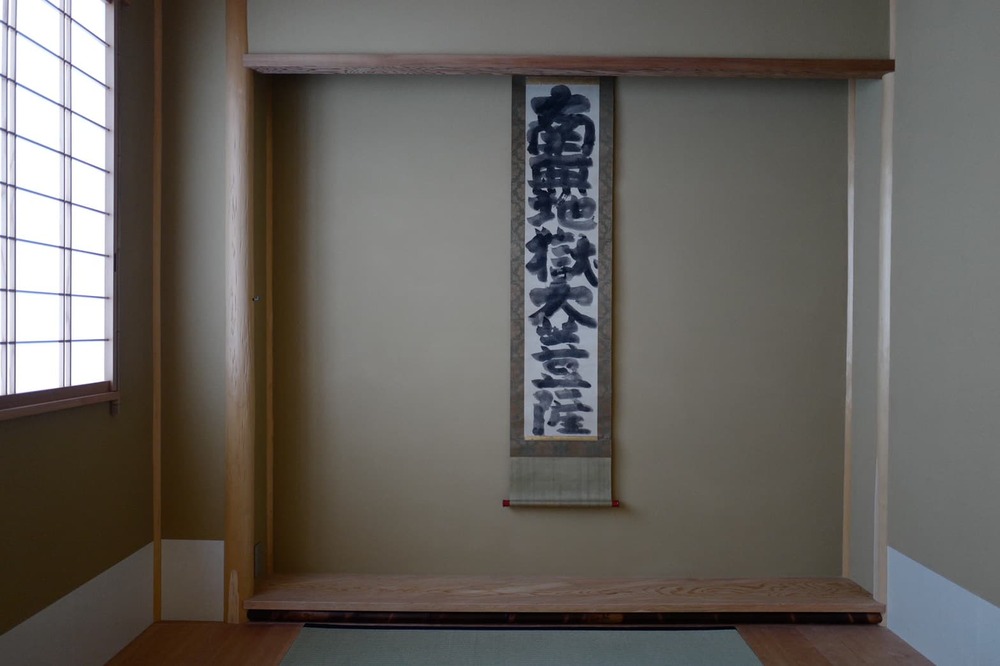

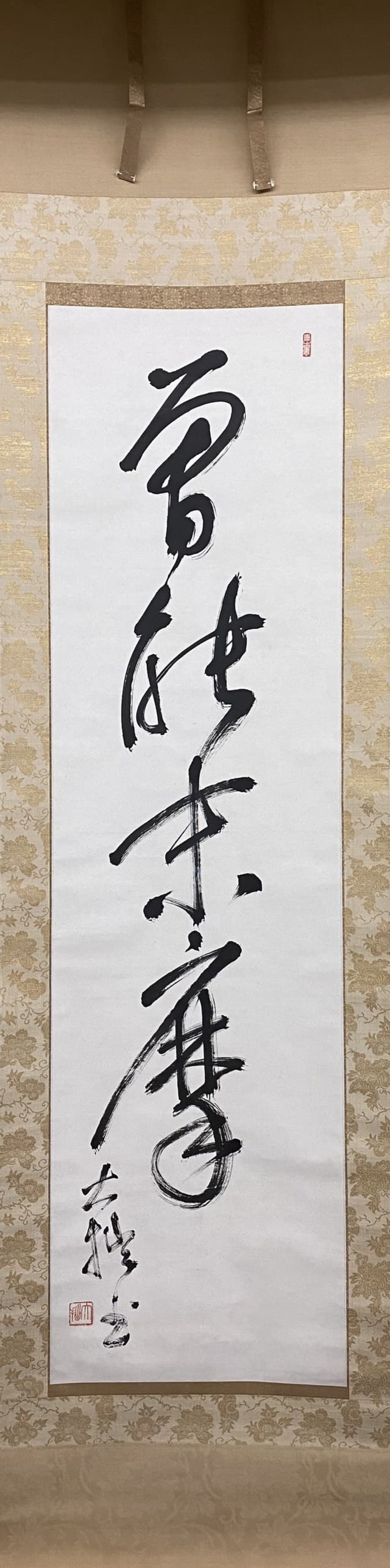

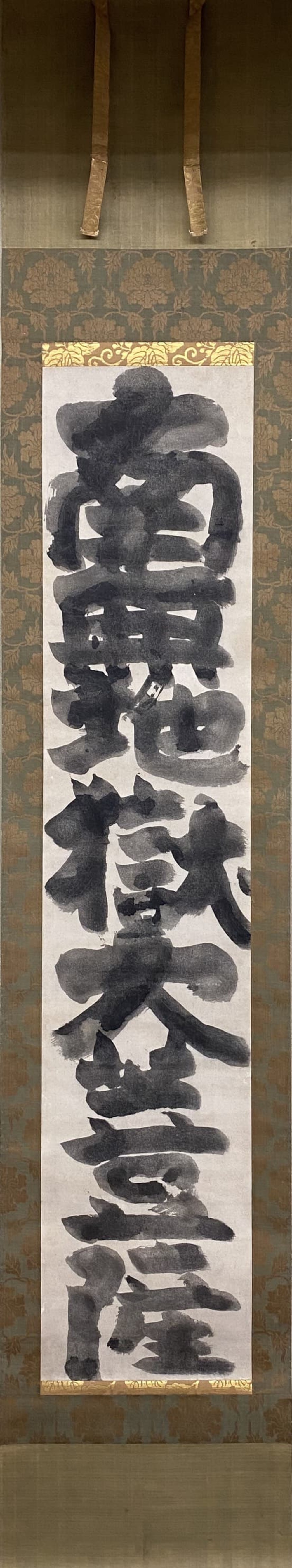

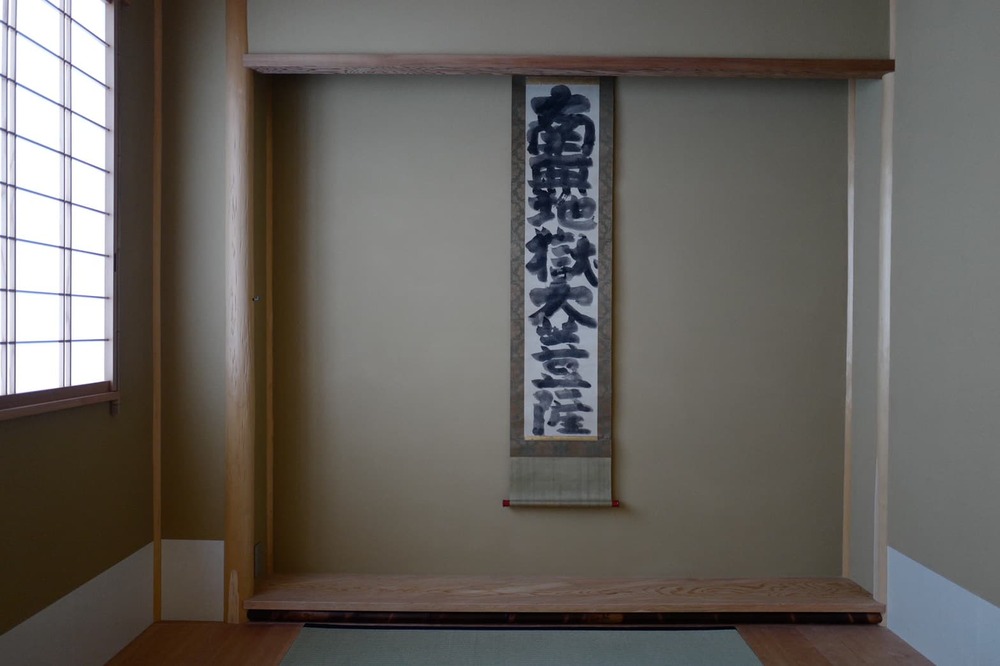

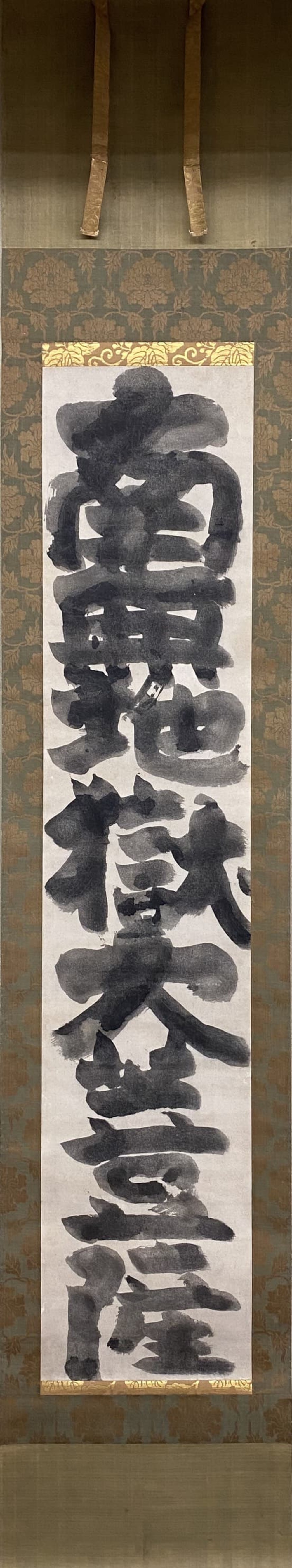

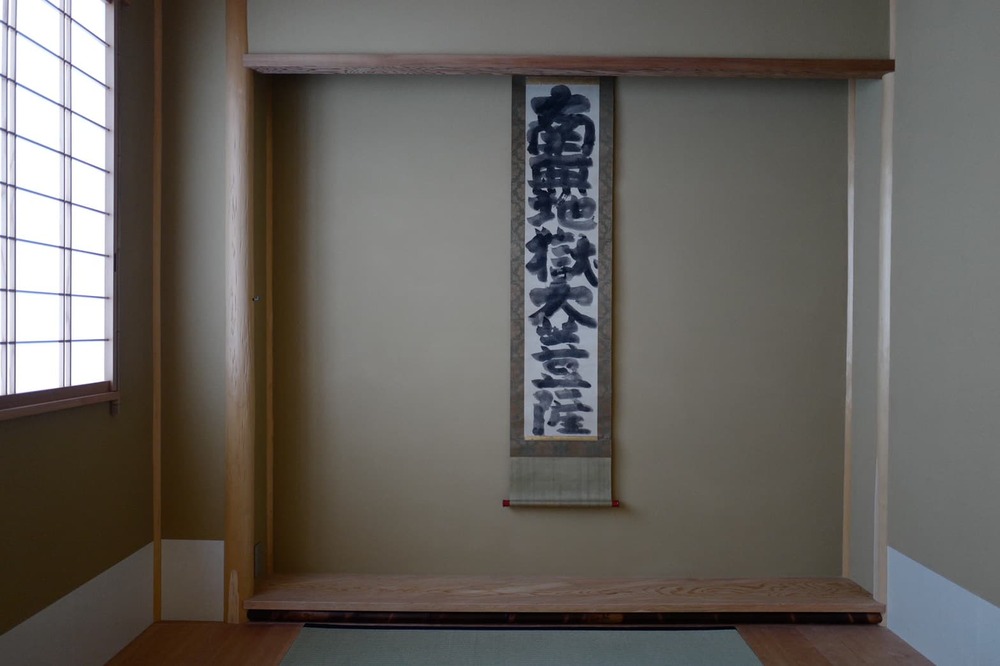

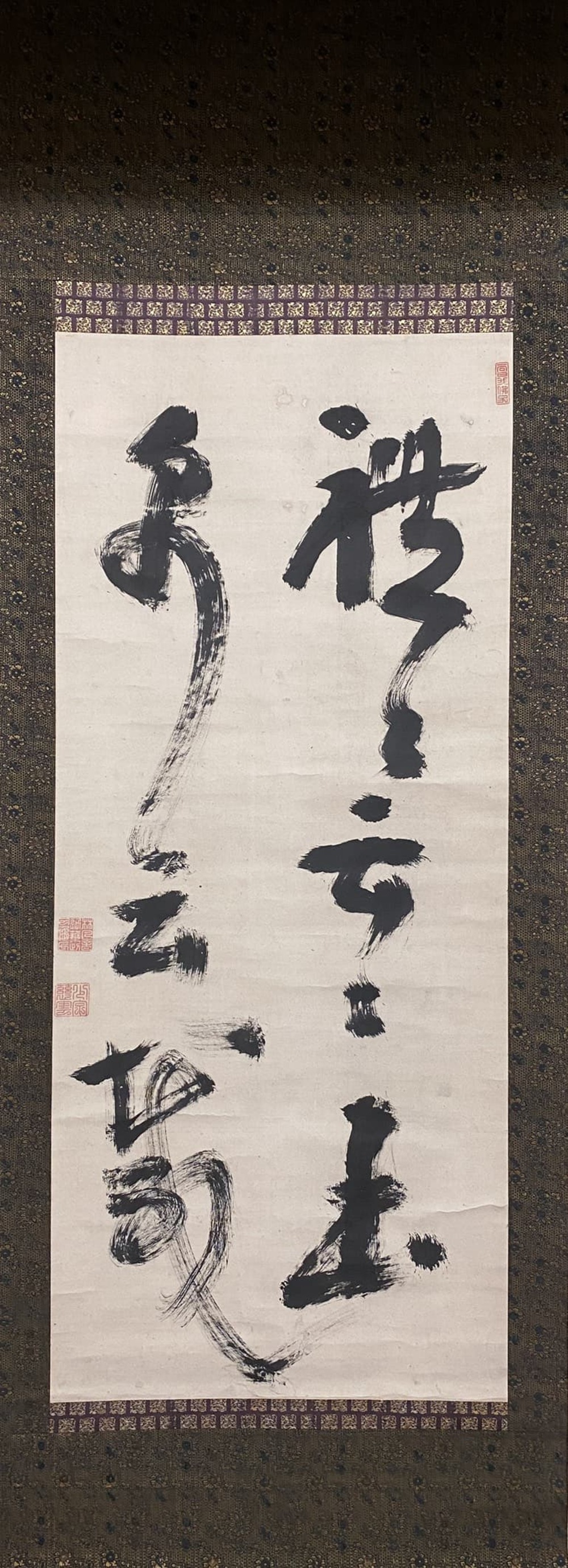

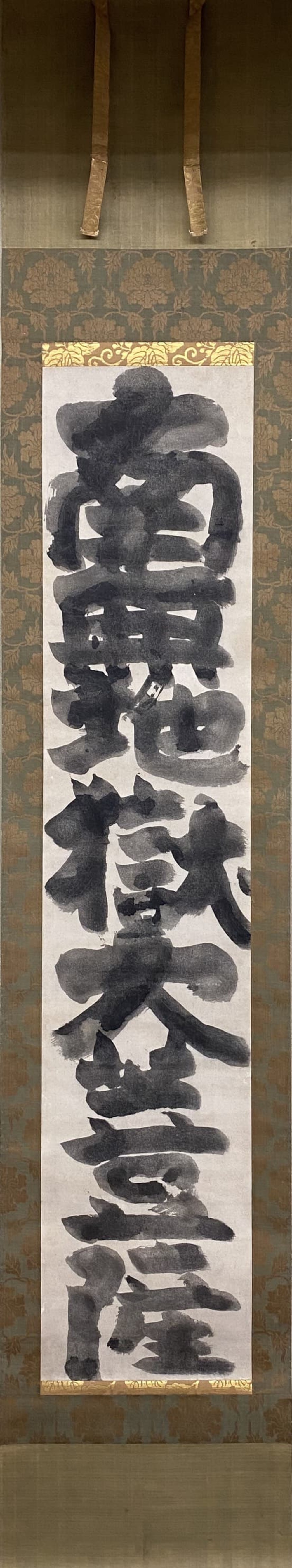

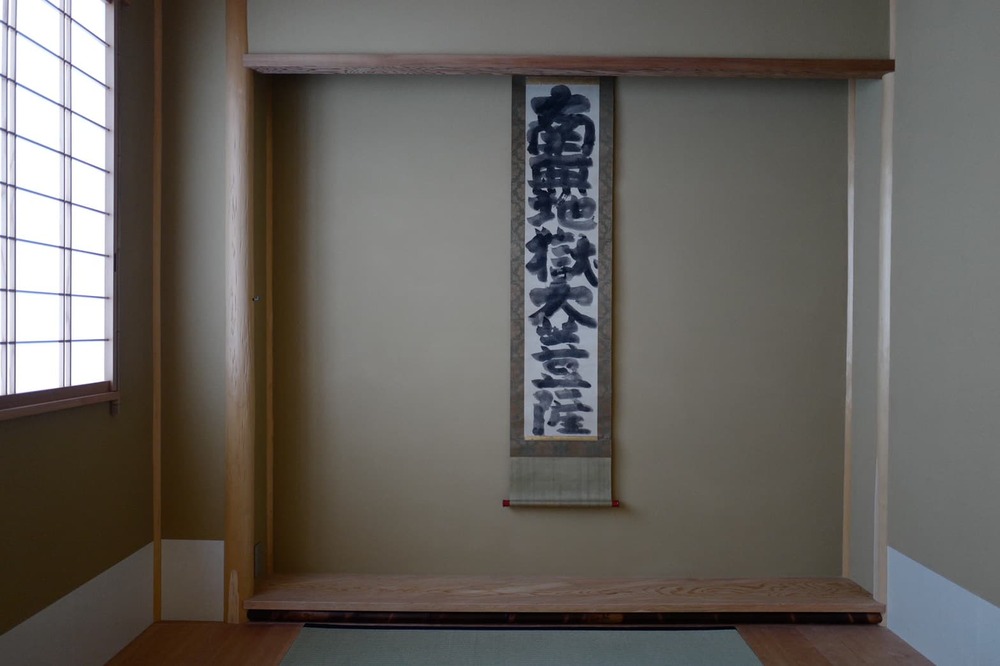

Hakuin Ekaku "Namu Jigoku Daibosatsu"

ink on paper

135.7cm×28cm / 213cm×39cm

Hakuin Ekaku "Namu Jigoku Daibosatsu"

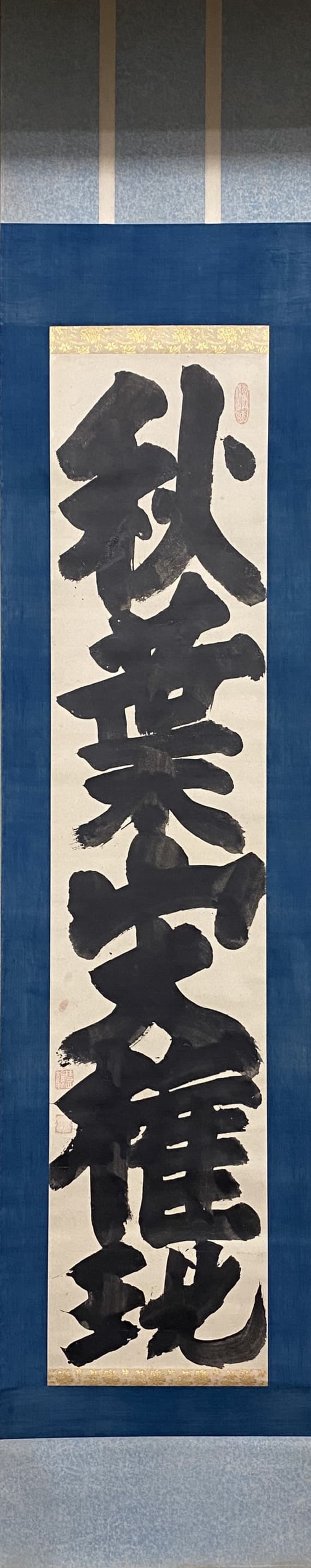

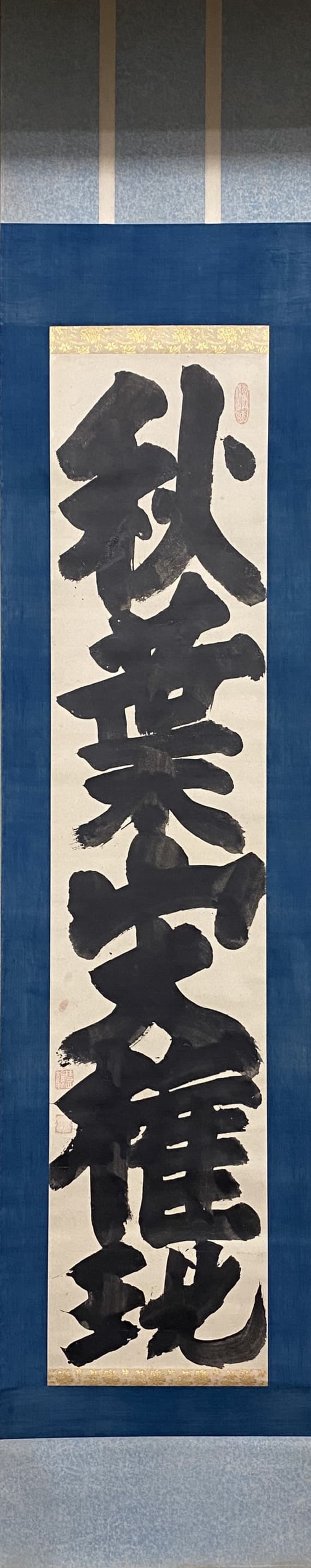

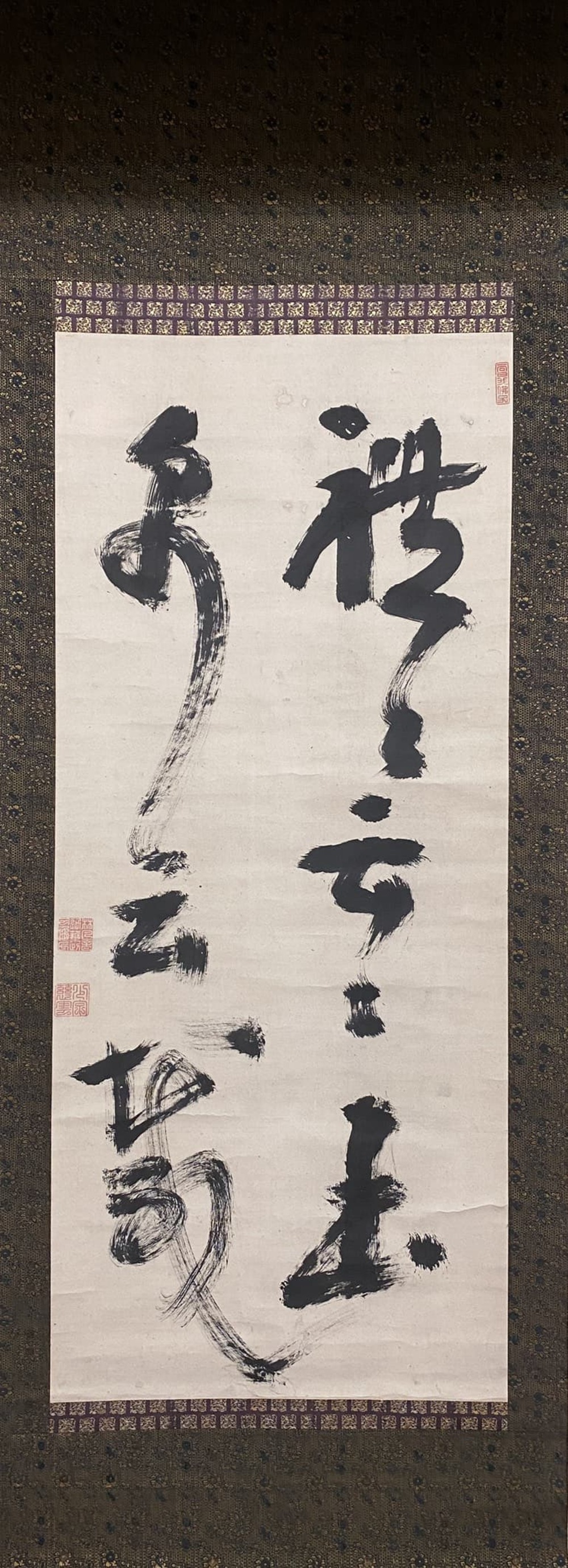

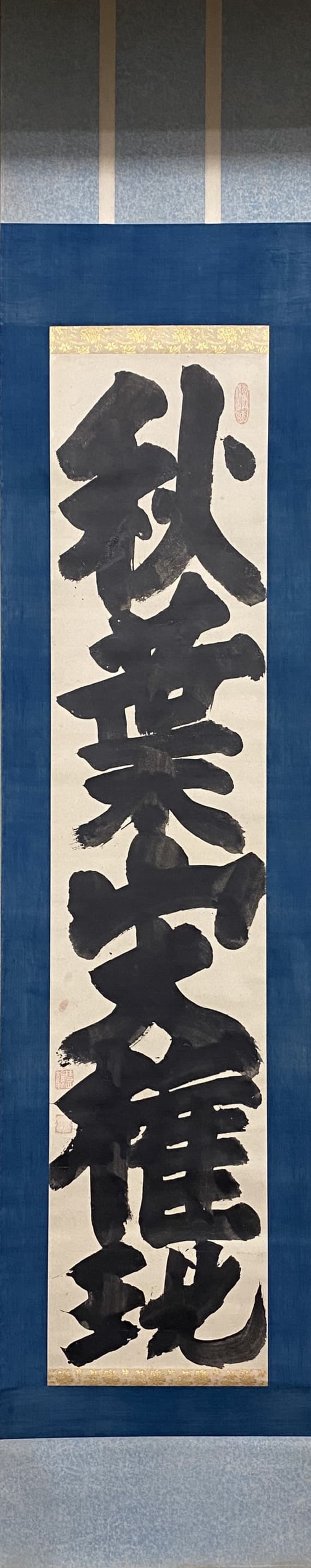

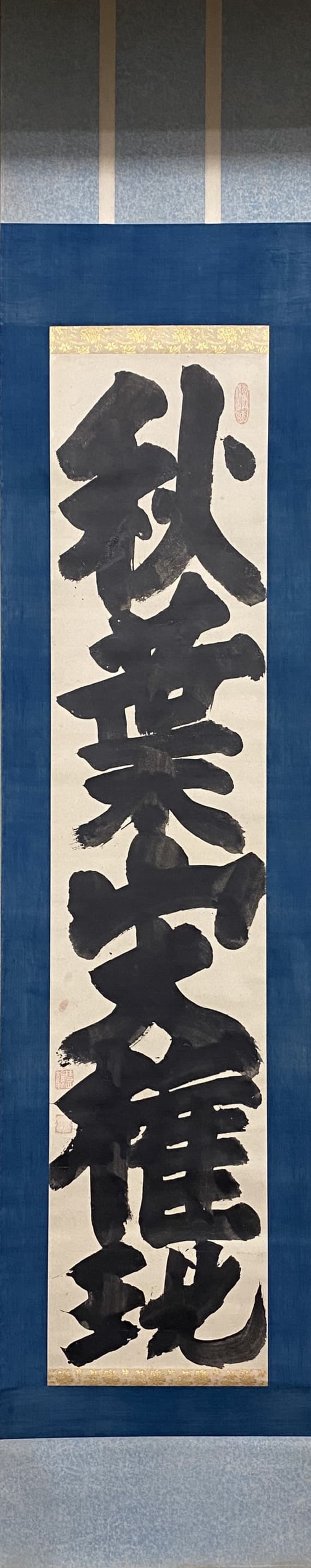

Hakuin Ekaku "Akihasan Daigongen"

ink on paper

132.5cm×28.5cm / 211cm×41.5cm

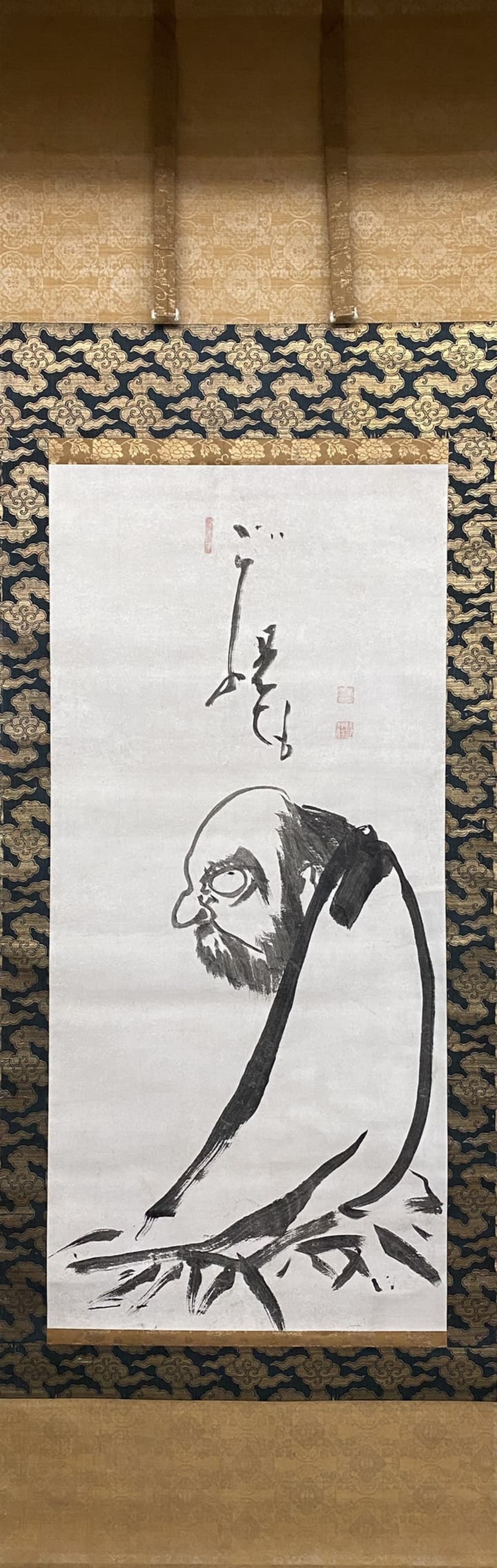

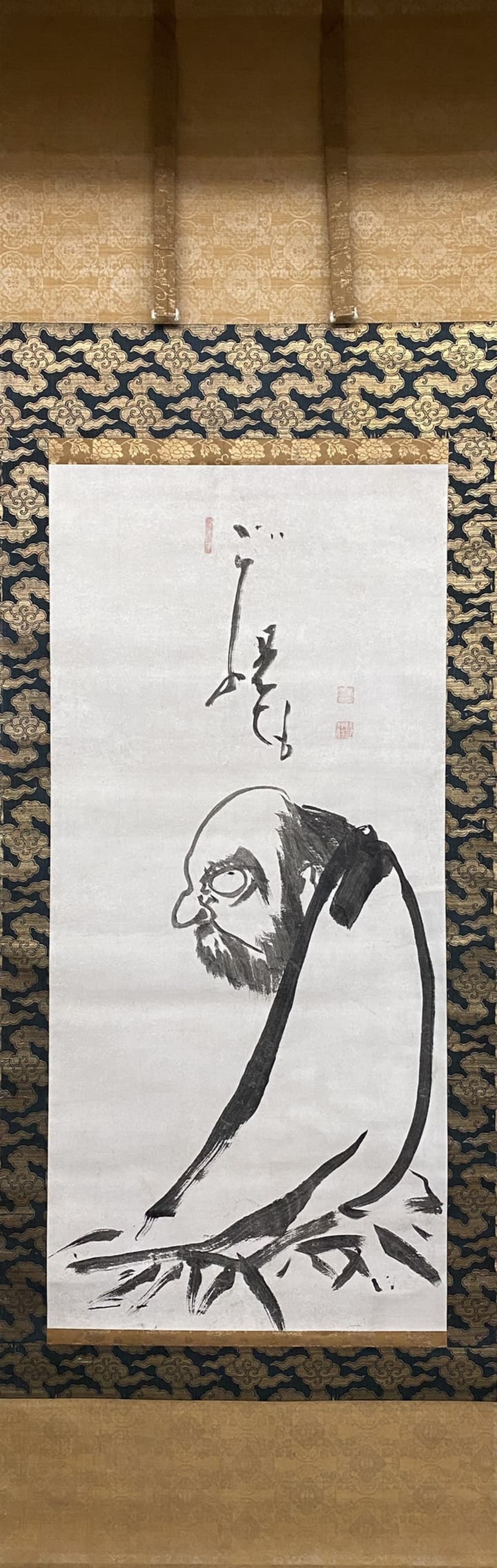

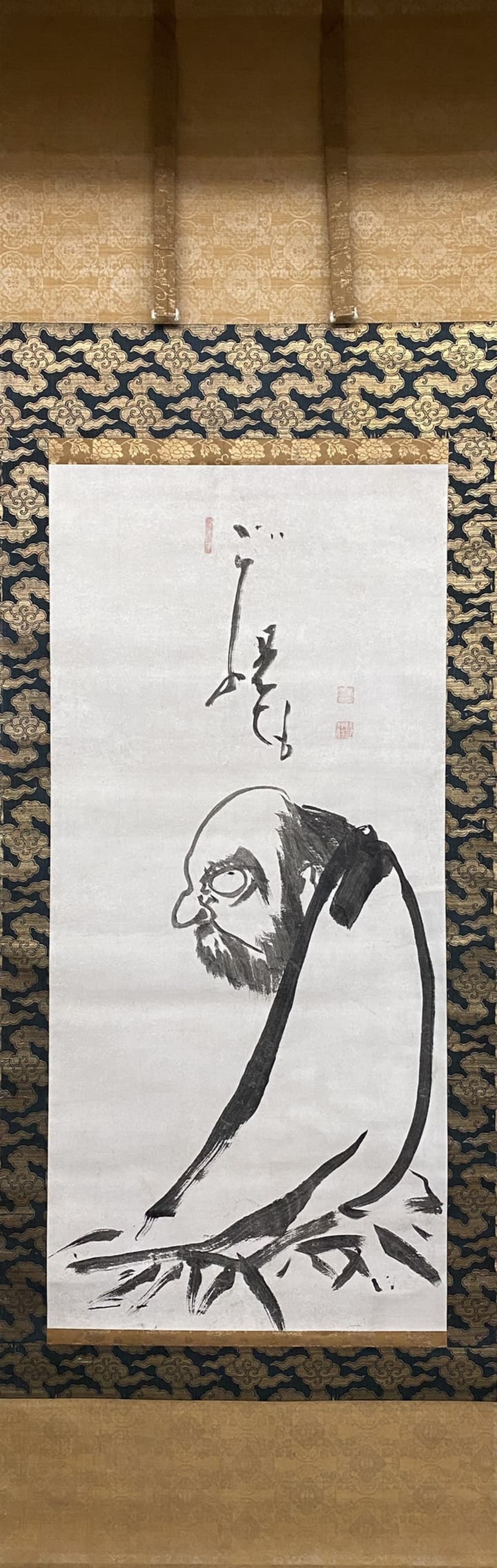

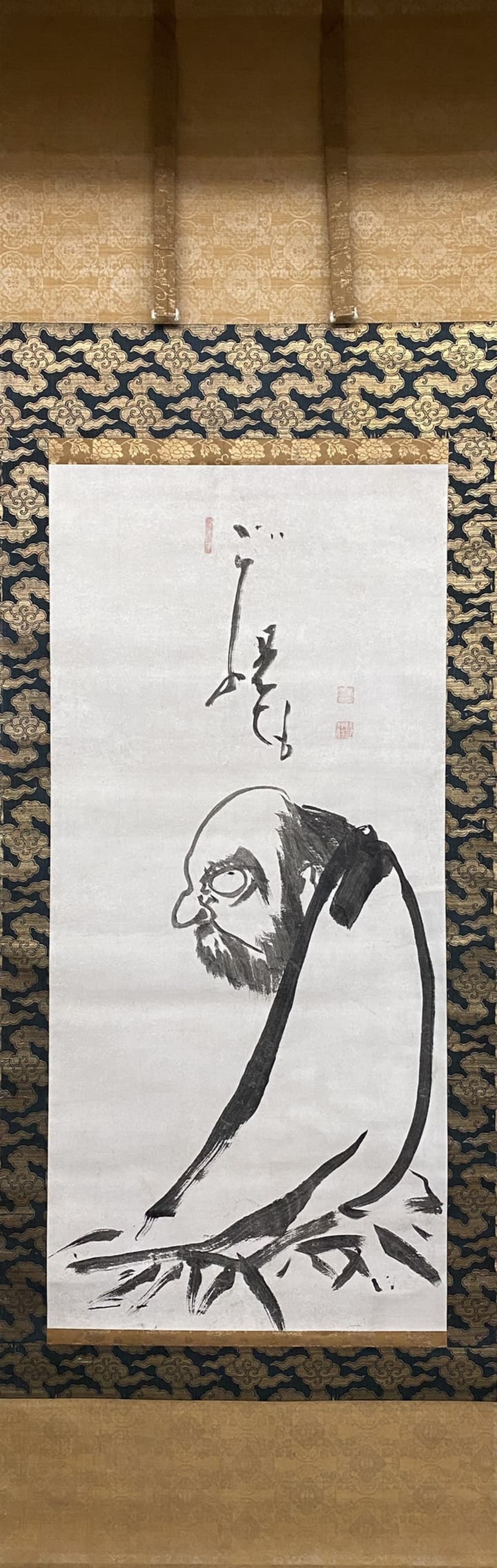

Hakuin Ekaku "Daruma"

ink on paper

118.5cm×54.5cm / 217cm×69cm

Hakuin Ekaku "Daruma"

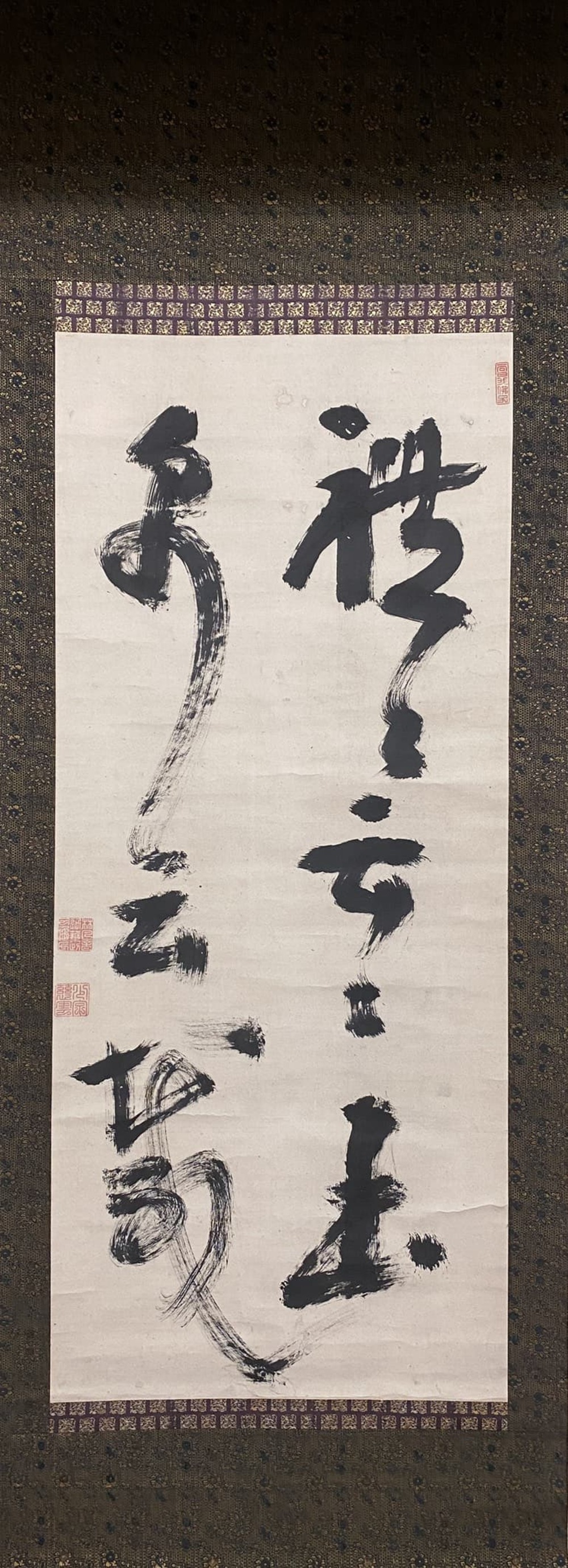

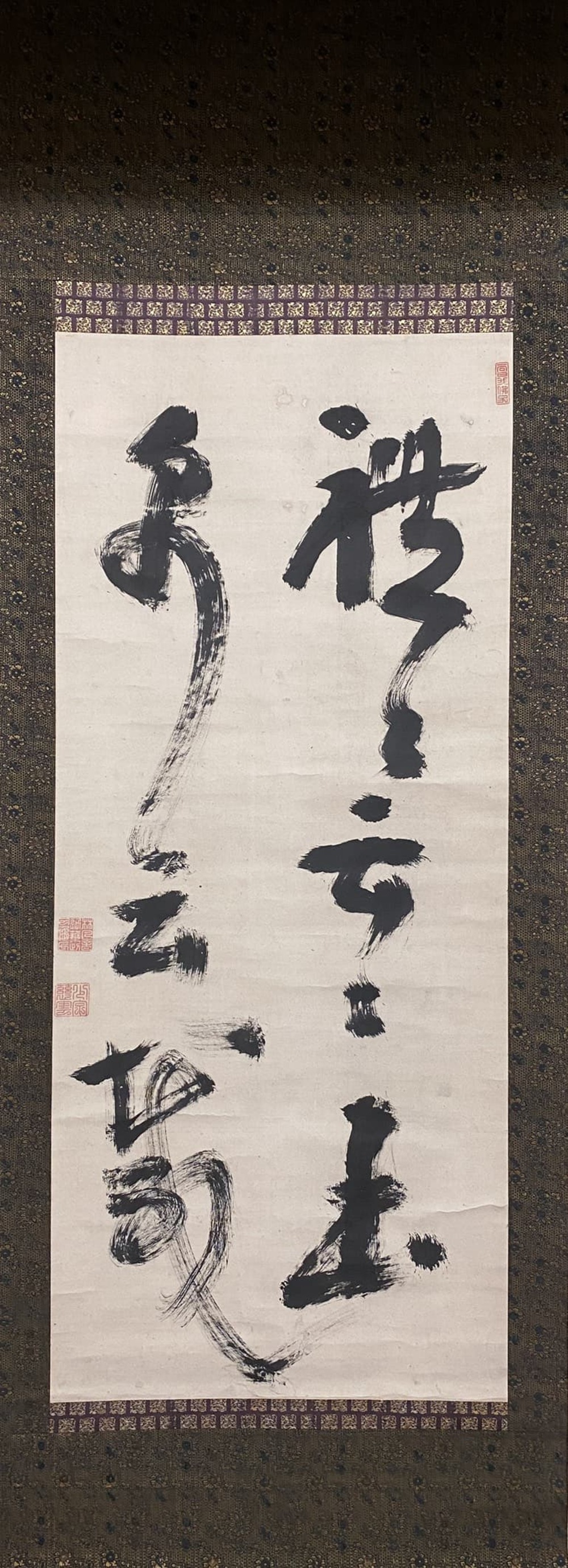

Jiun Onko "Calligraphy"

ink on paper

120.3cm×50.5cm / 182cm×66.5cm

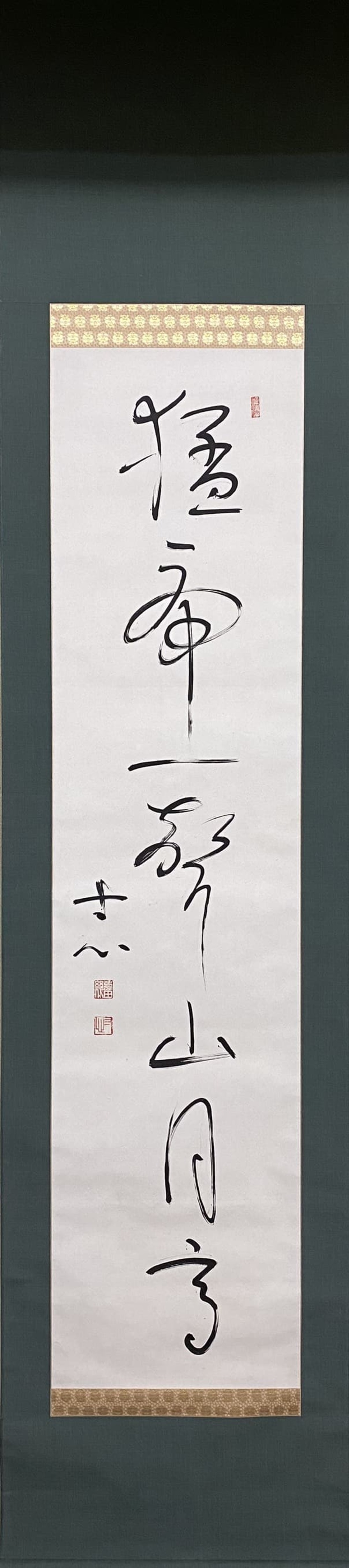

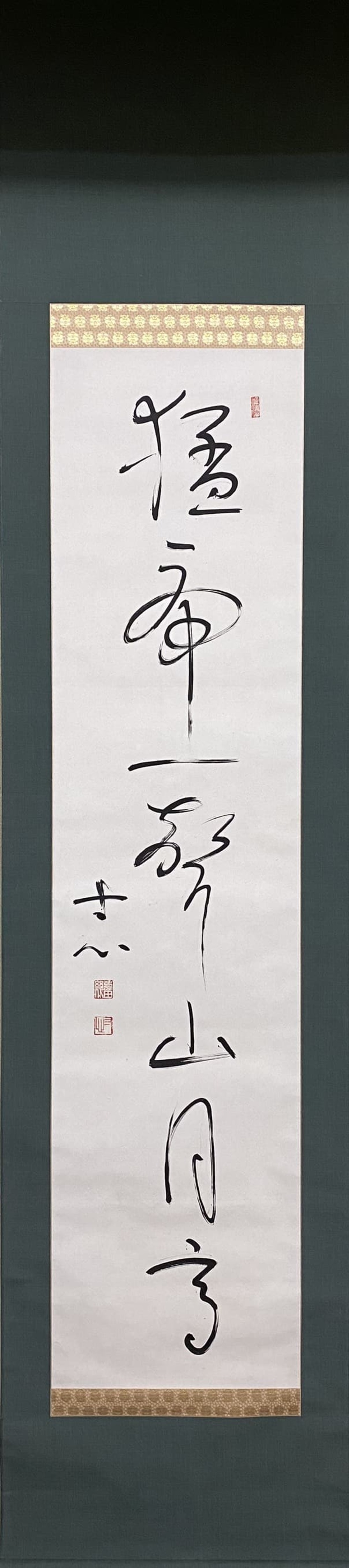

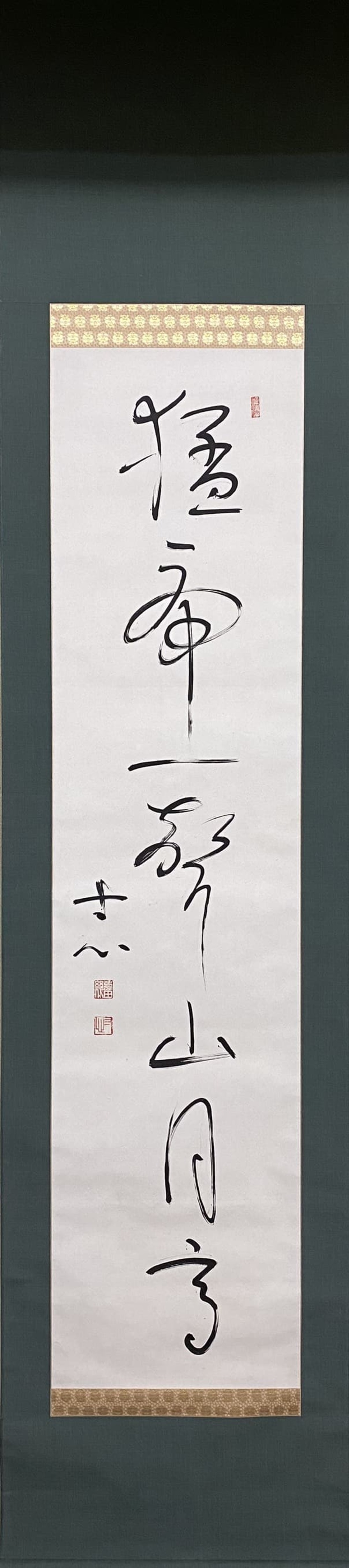

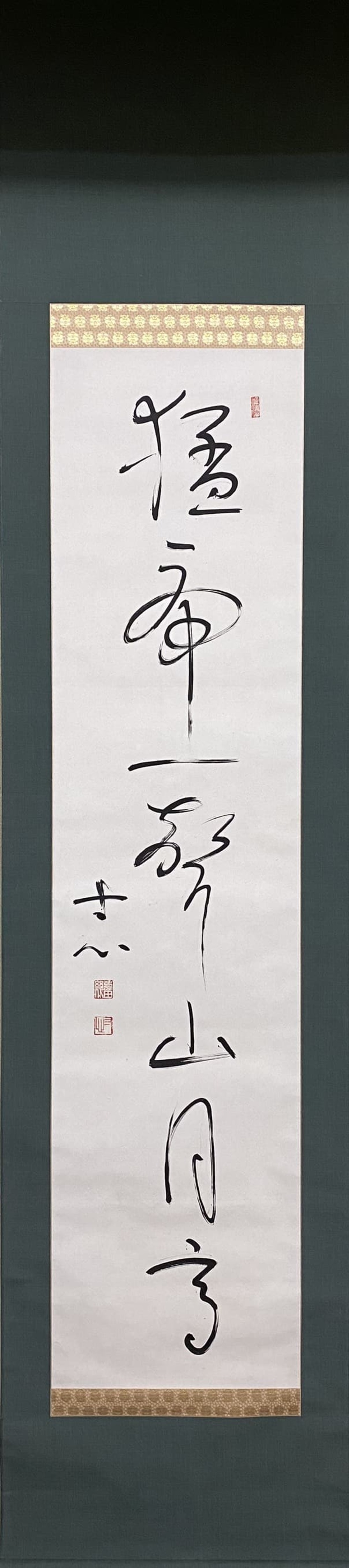

Nisida Kitaro "Calligraphy"

ink on paper

135cm×32cm / 205cm×45.5cm

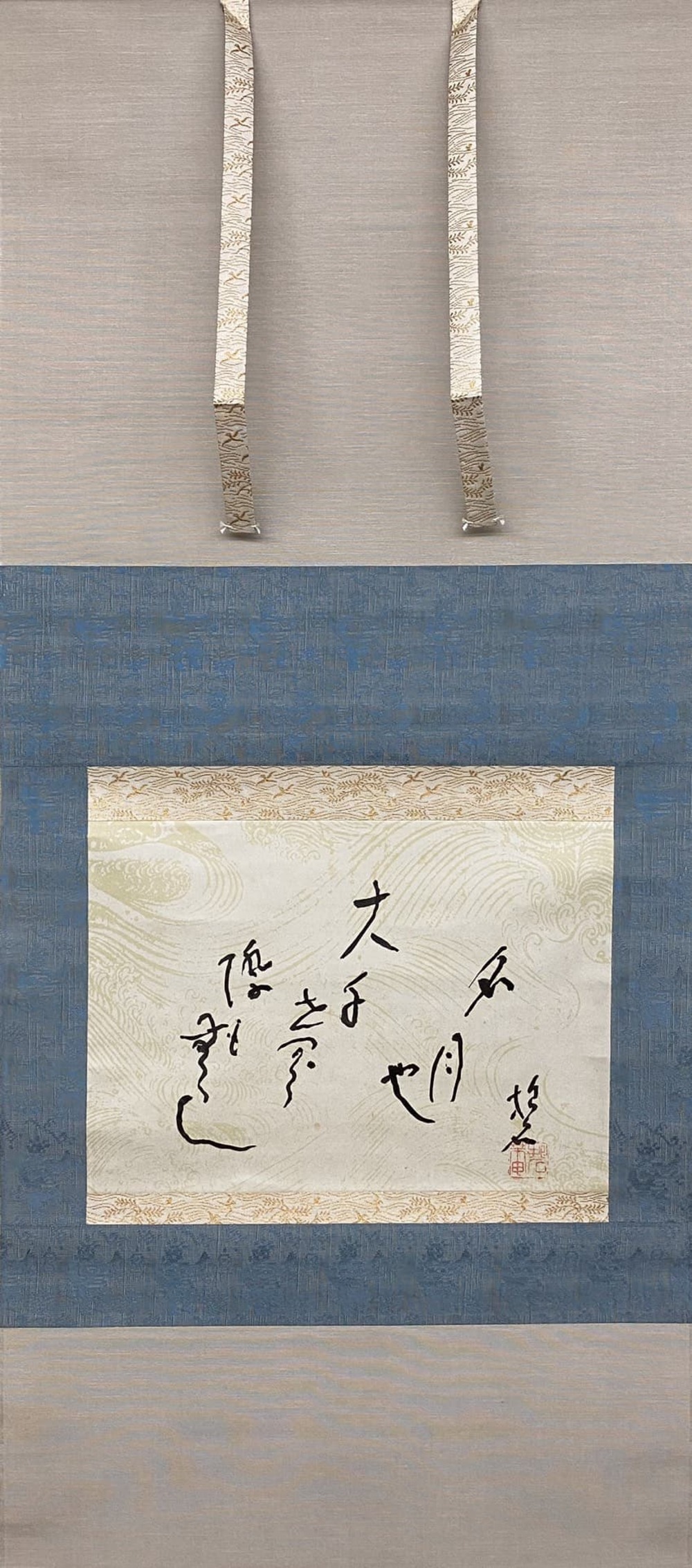

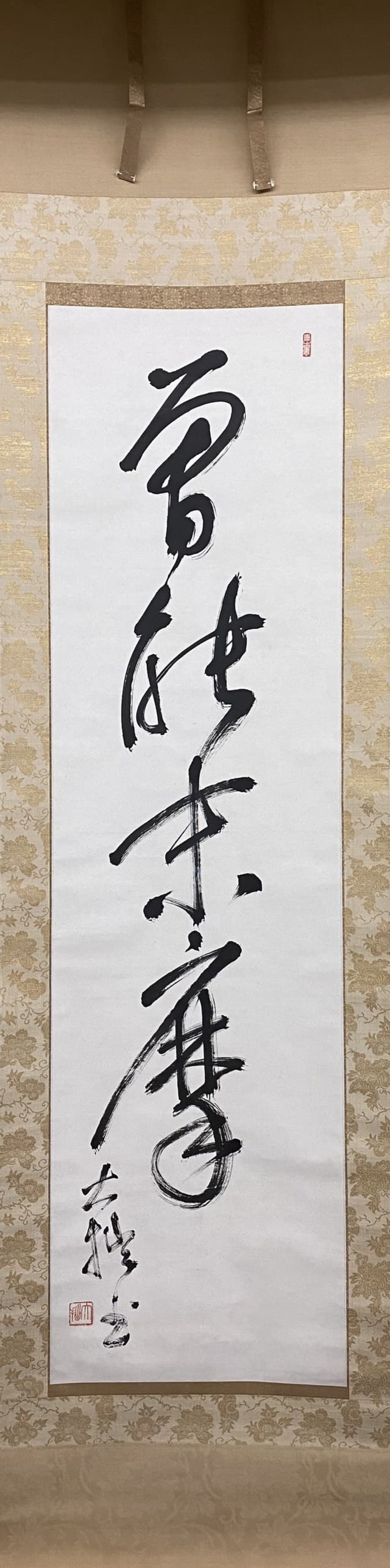

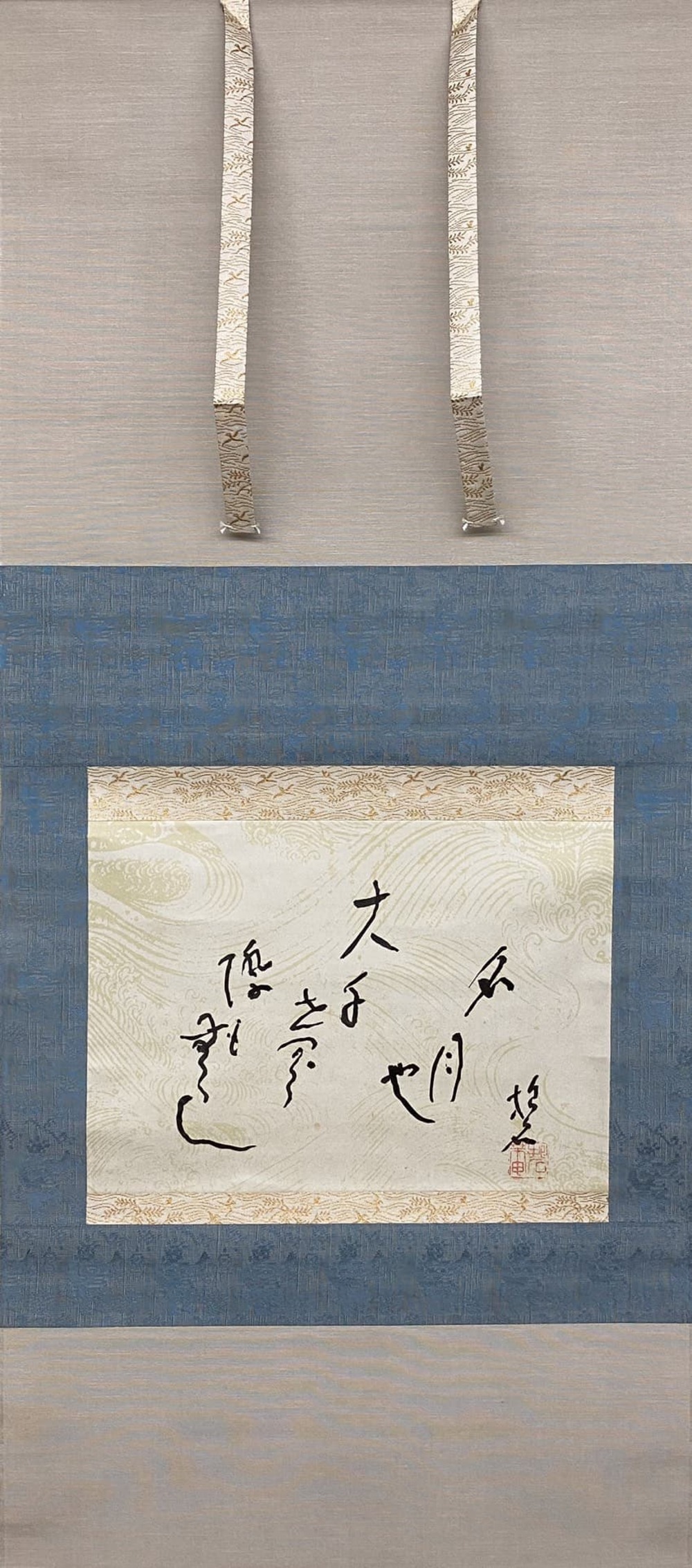

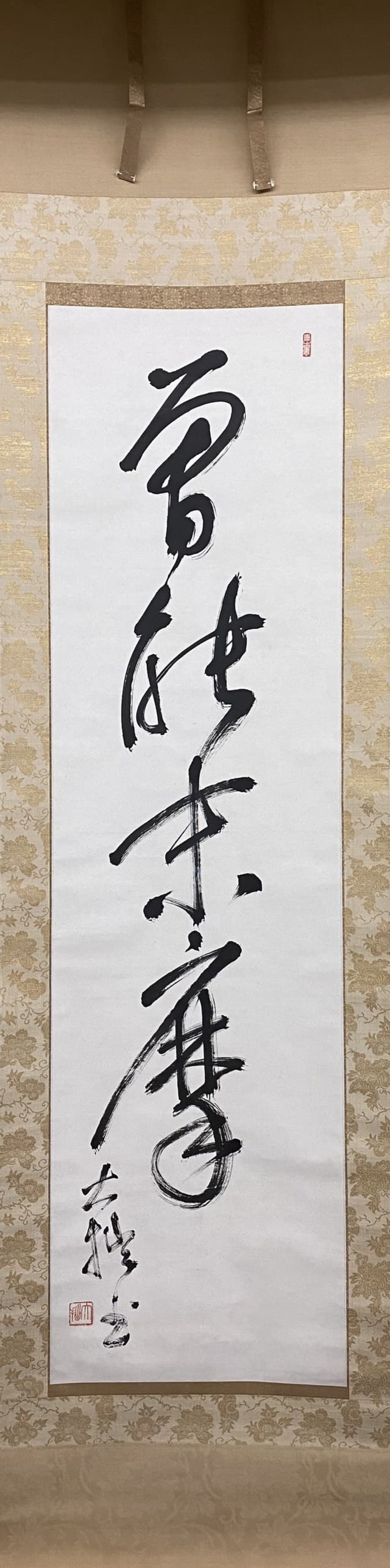

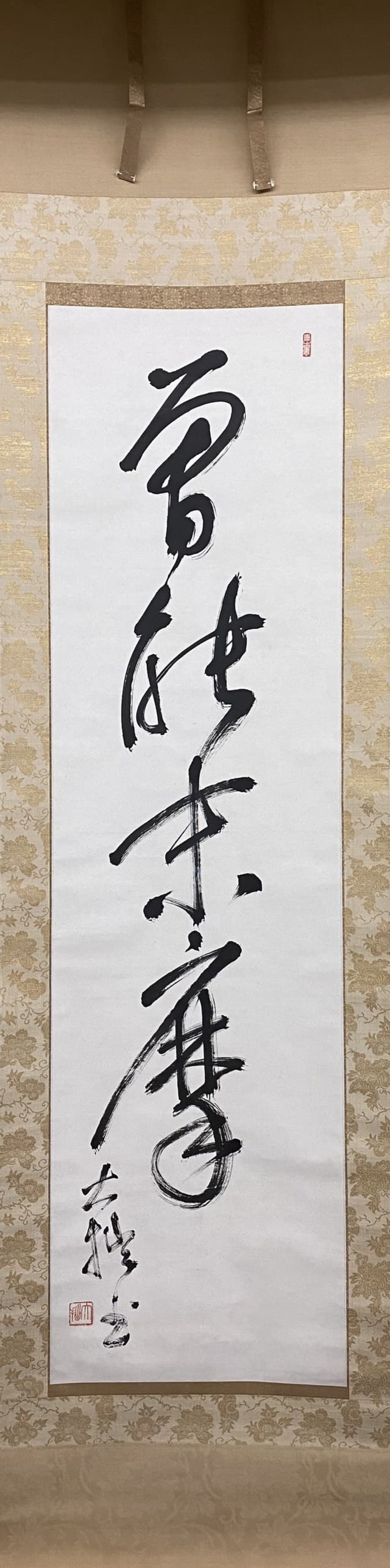

Suzuki Daisetsu "Calligraphy"

ink on paper, with a box signed and sealed by Seki Bokuo

144.5cm×39.5cm / 222cm×53.5cm

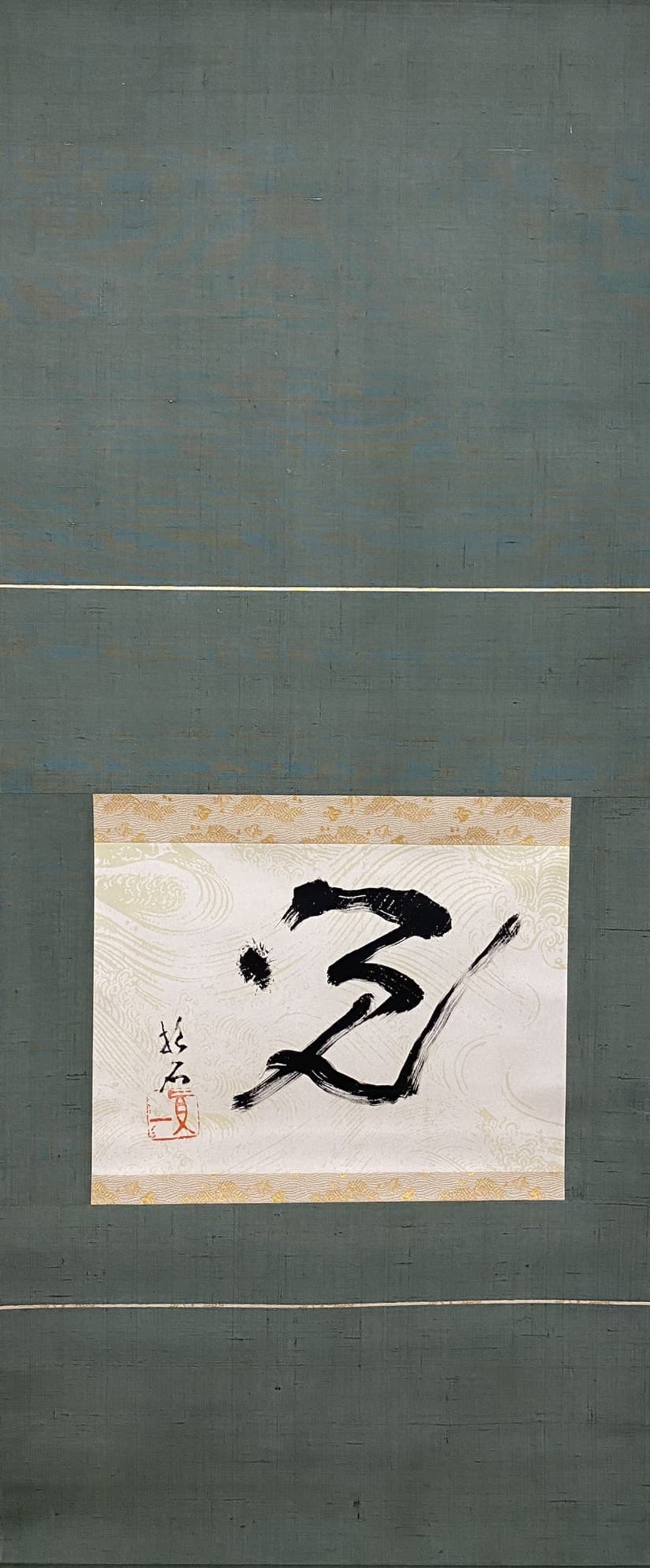

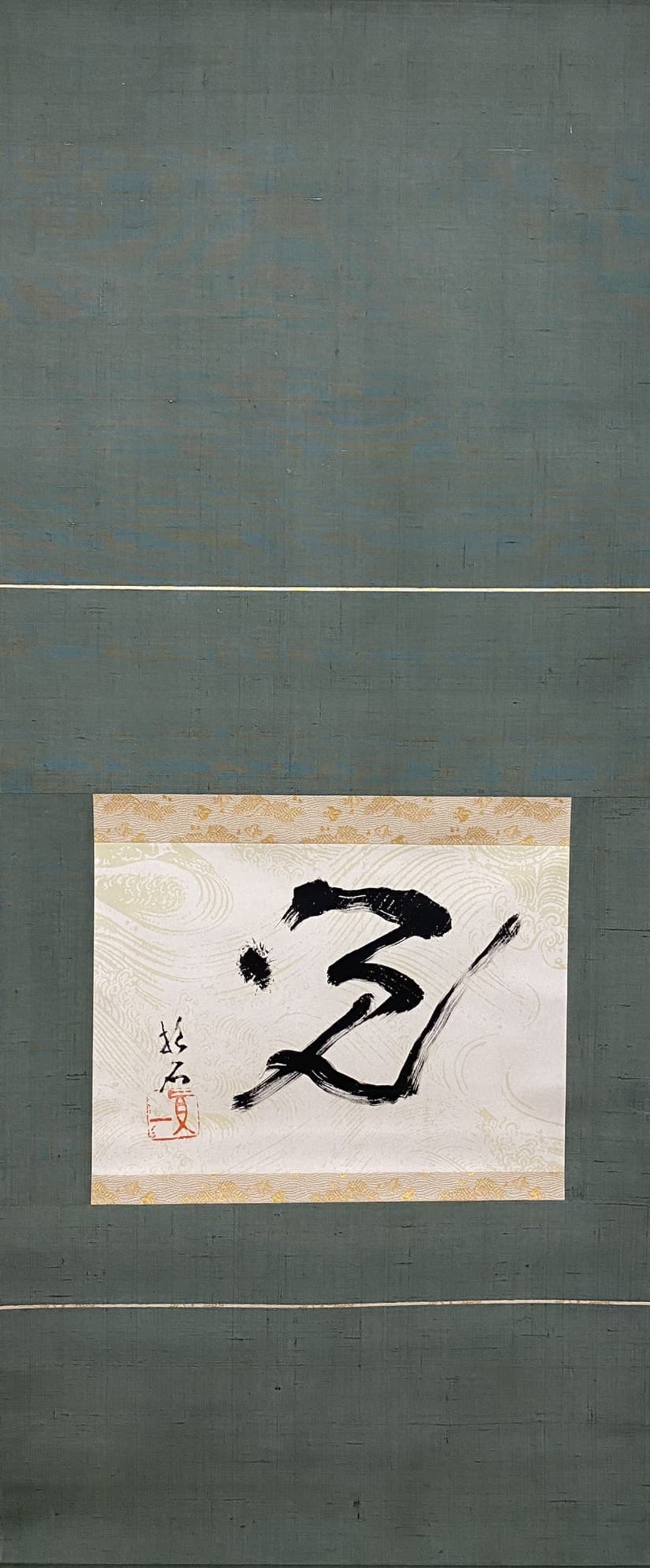

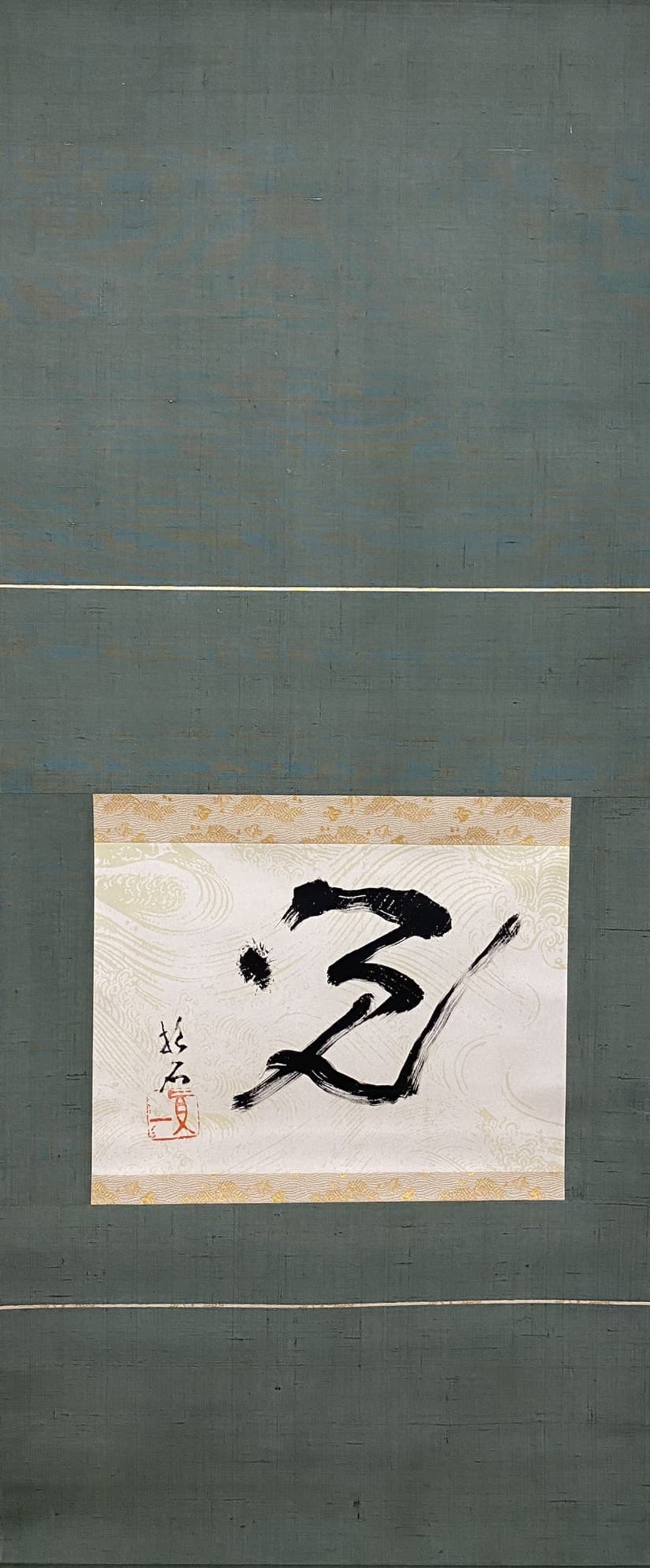

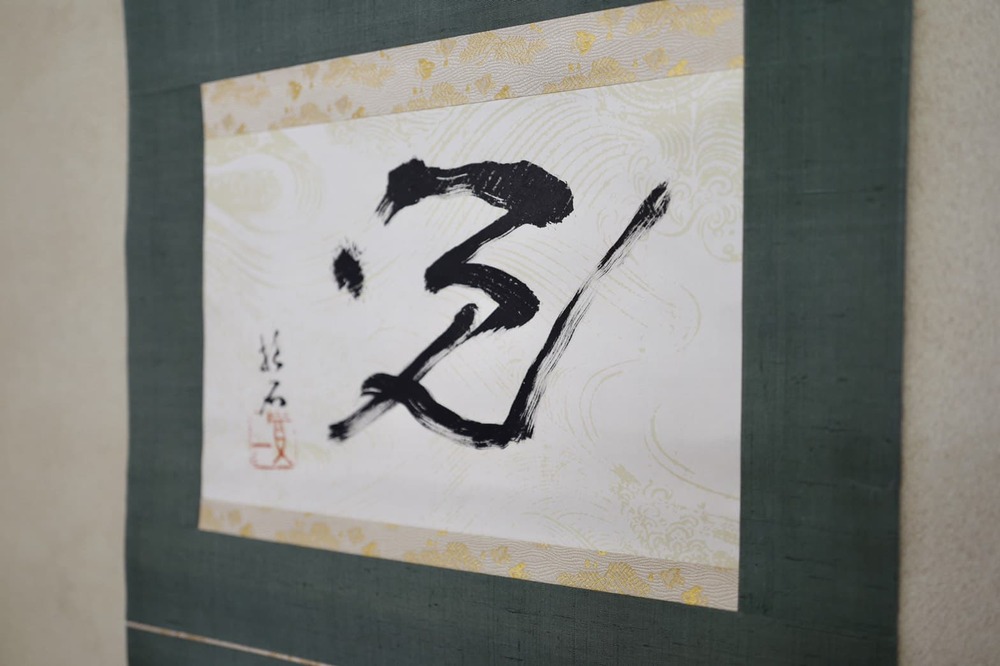

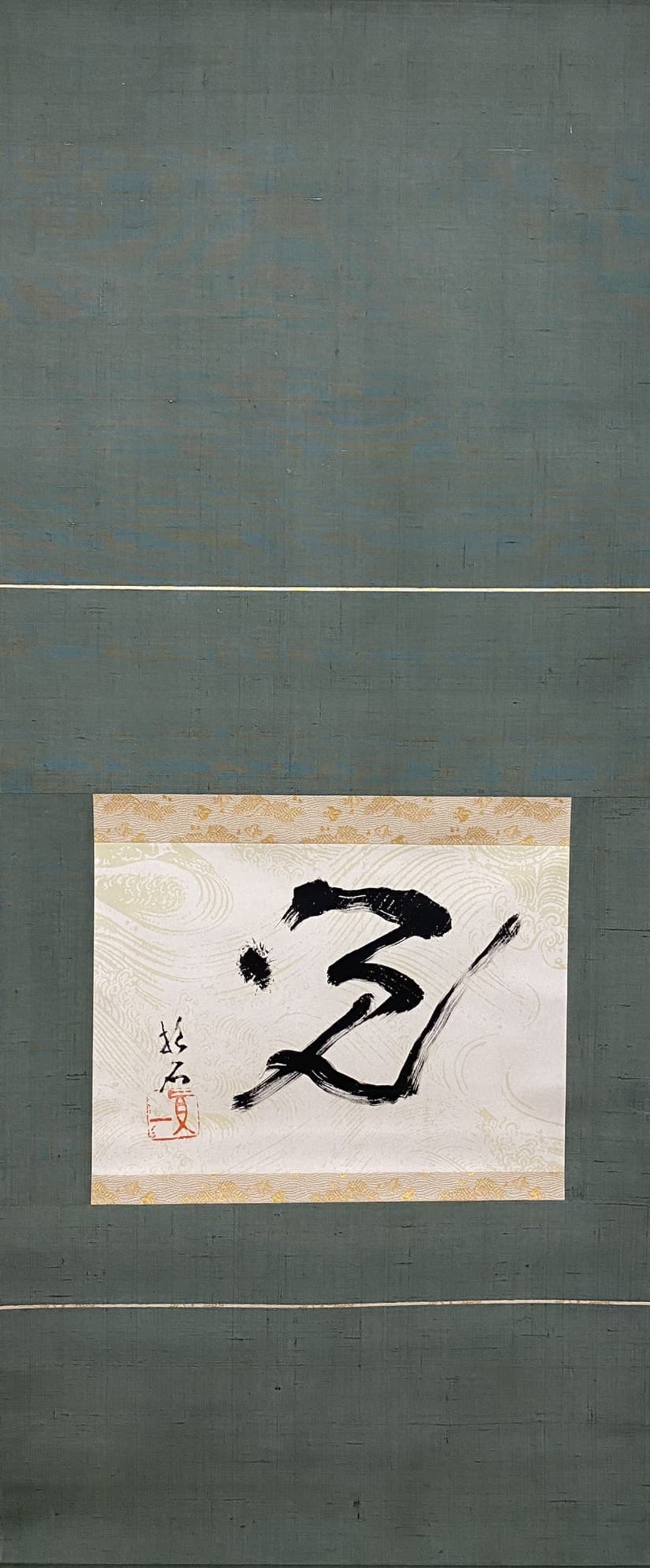

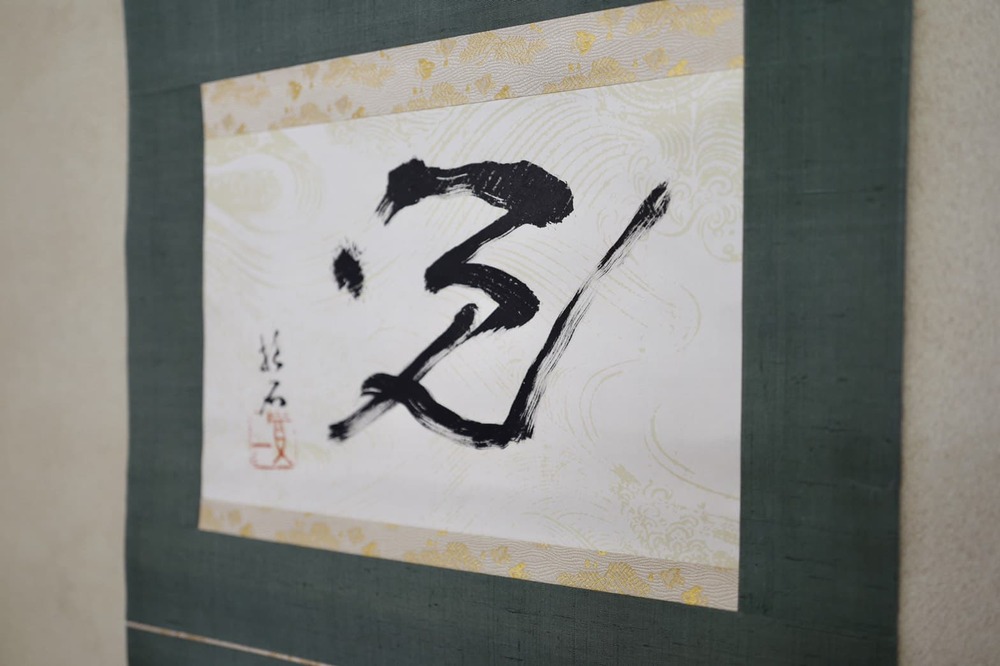

Hisamatsu Shinichi "Kaku"

ink on paper, with a box signed and sealed by the artist

22cm×31.6cm / 107cm×44.5cm

Hisamatsu Shinichi "Kaku"

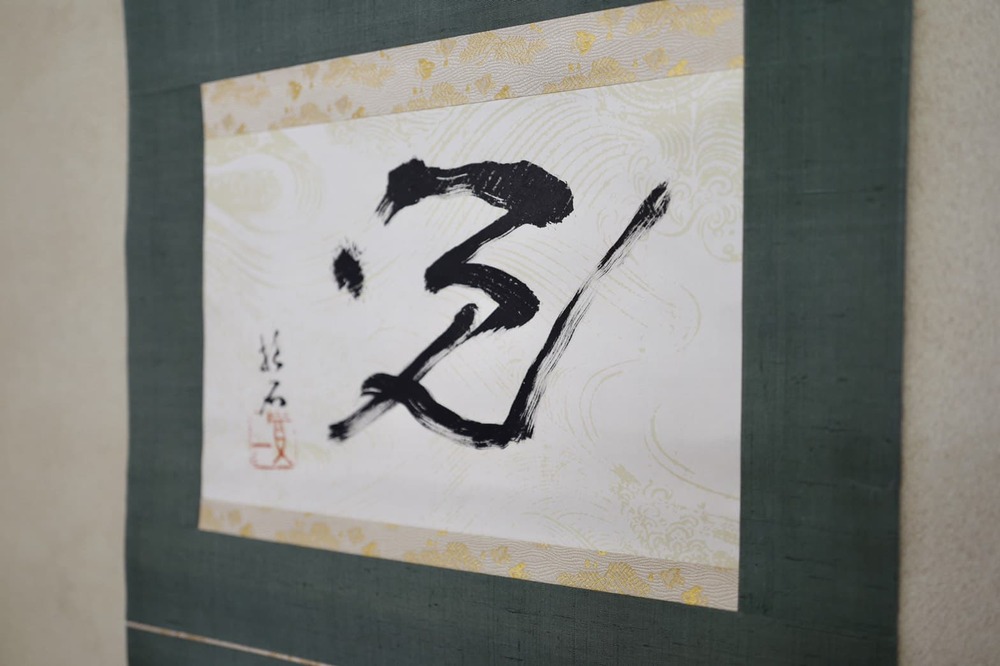

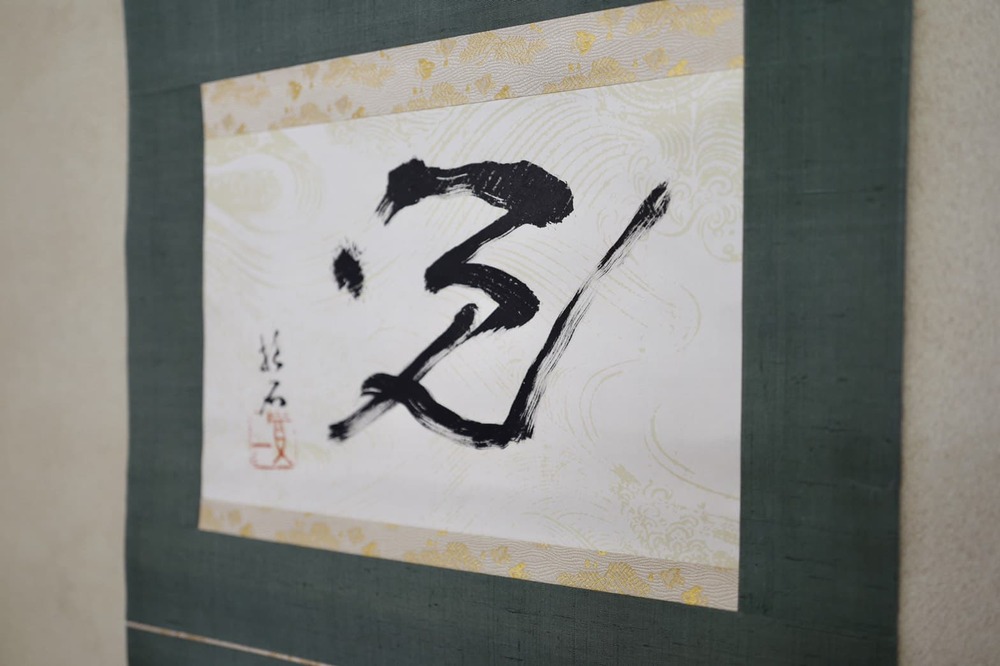

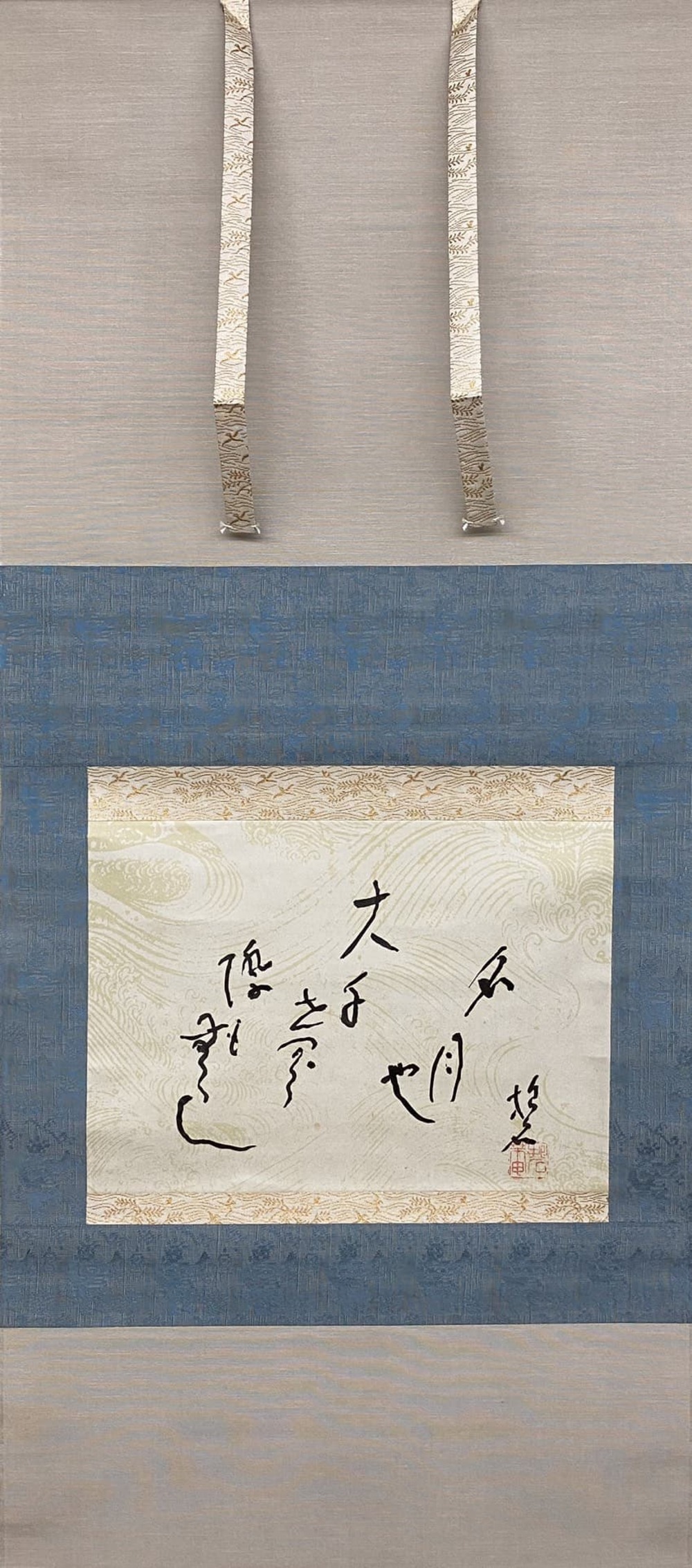

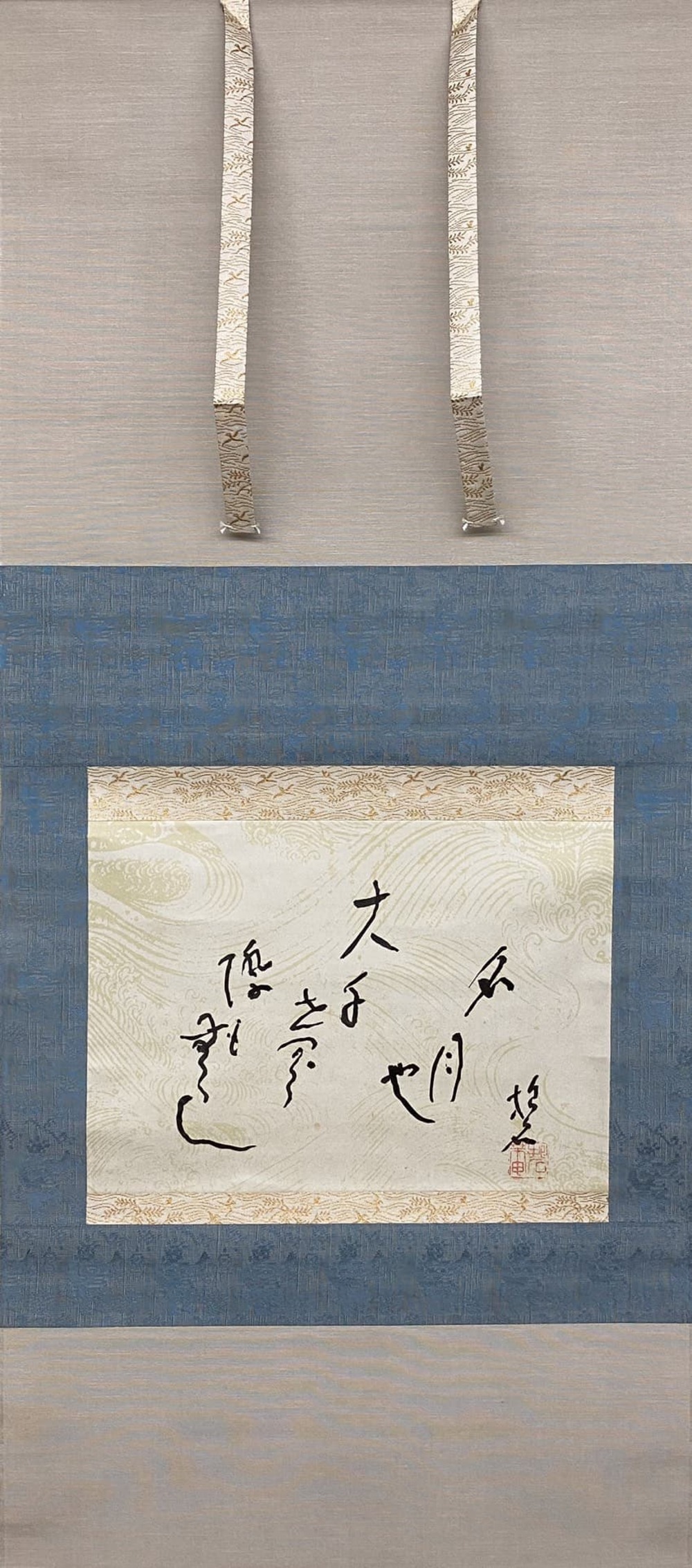

Hisamatsu Shinichi "Meigetsuya"

ink on paper

22.5cm×31.5cm / 99cm×42cm

Hisamatsu Shinichi "Meigetsuya"

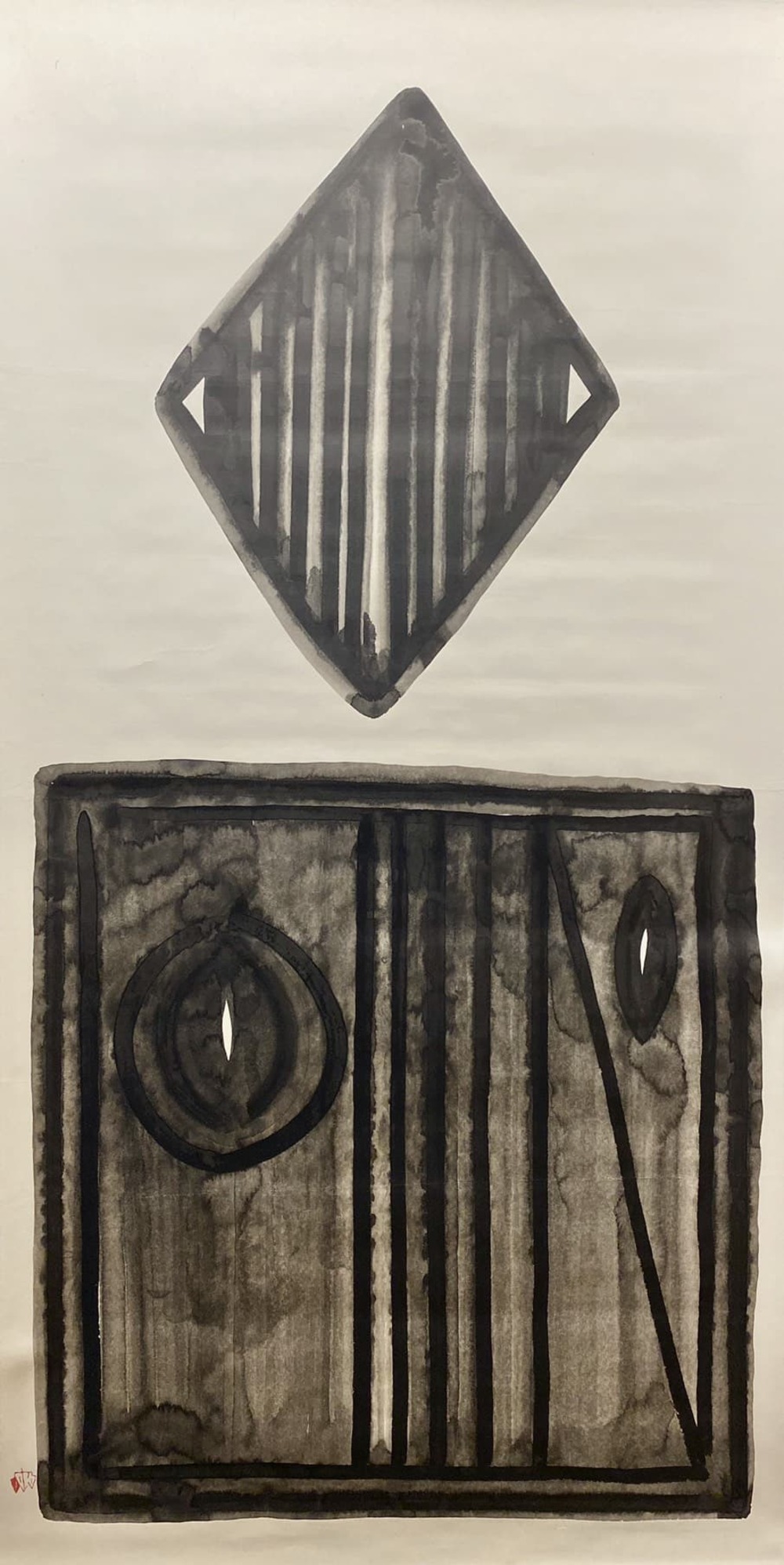

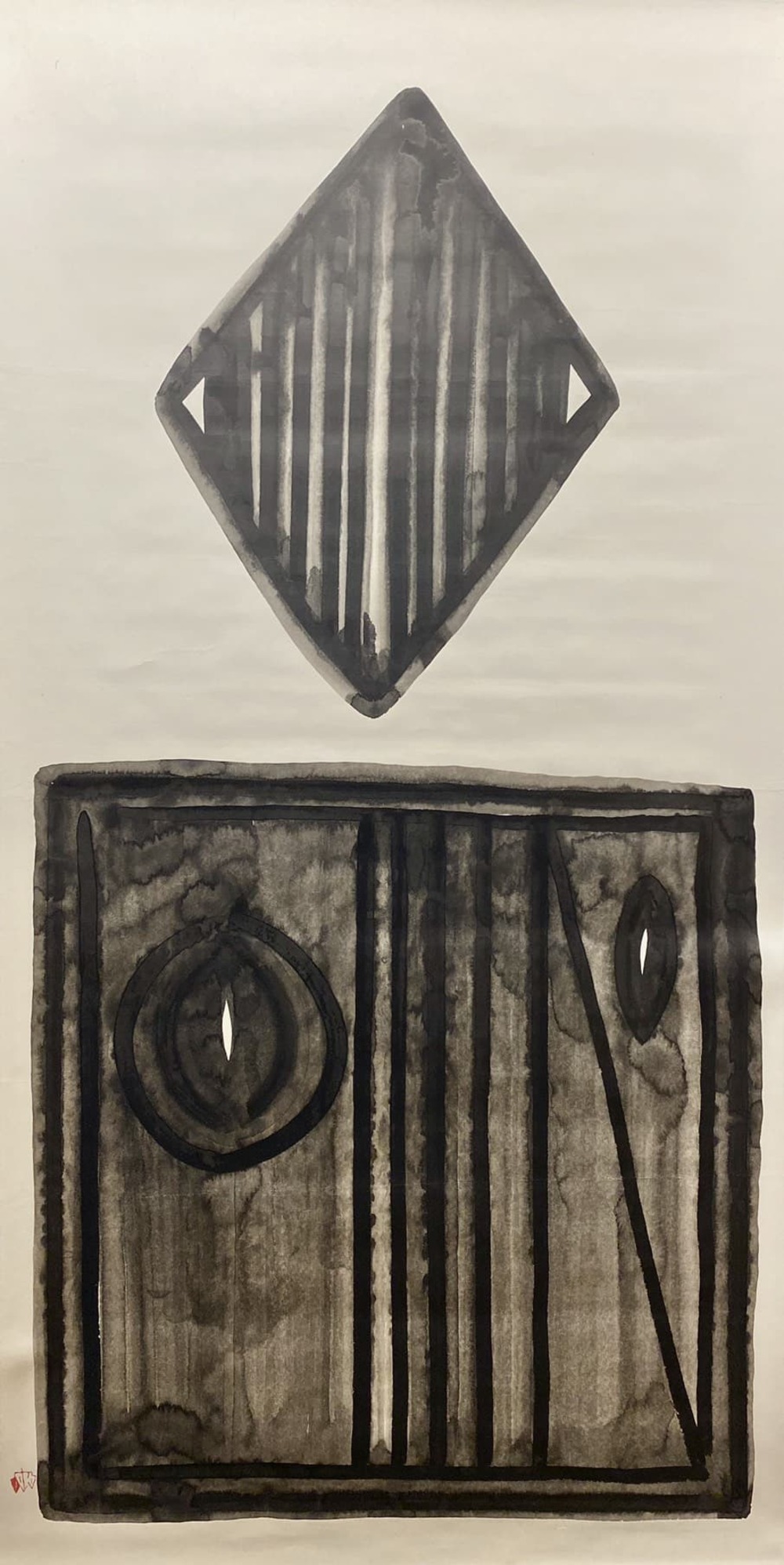

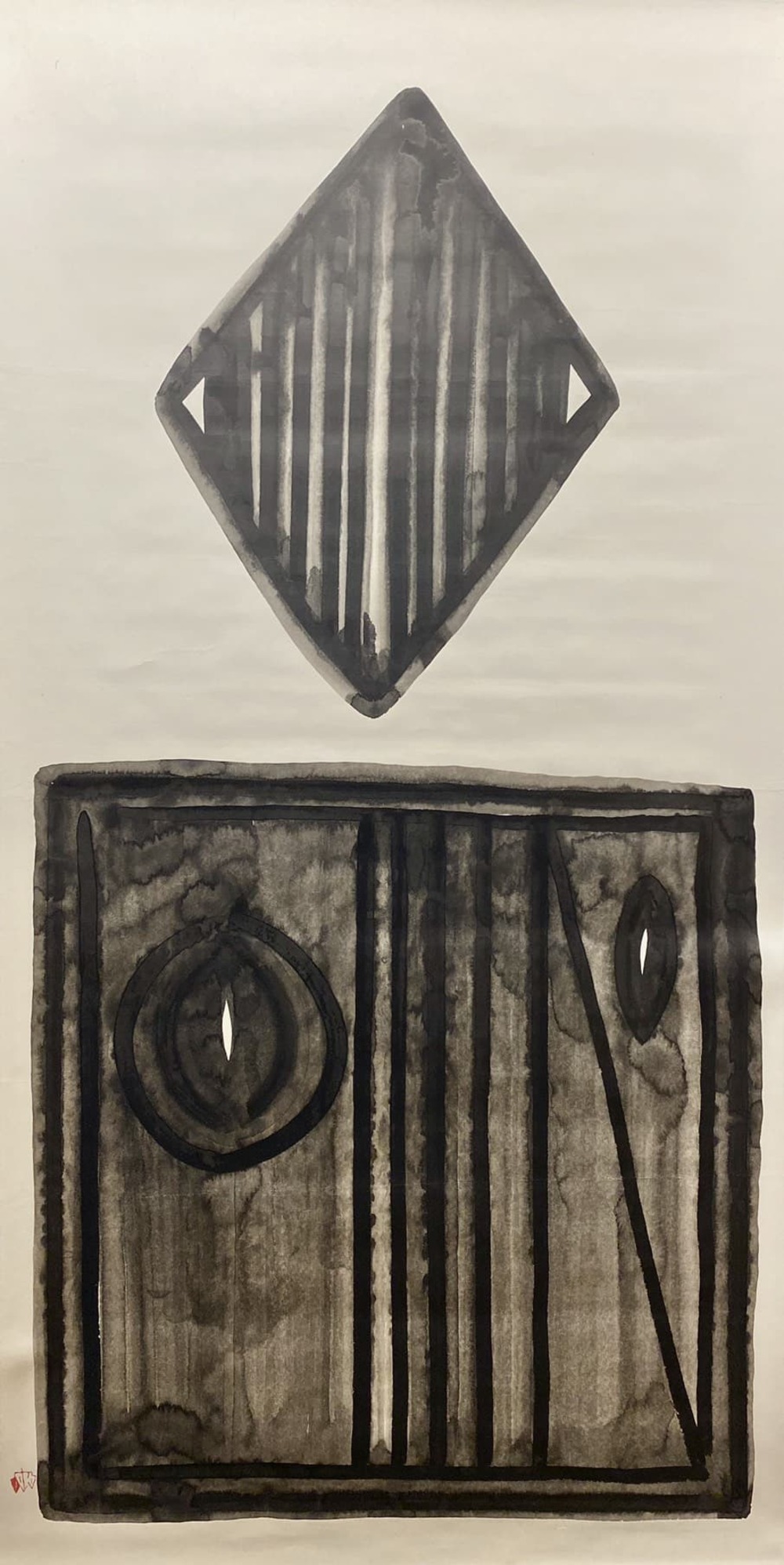

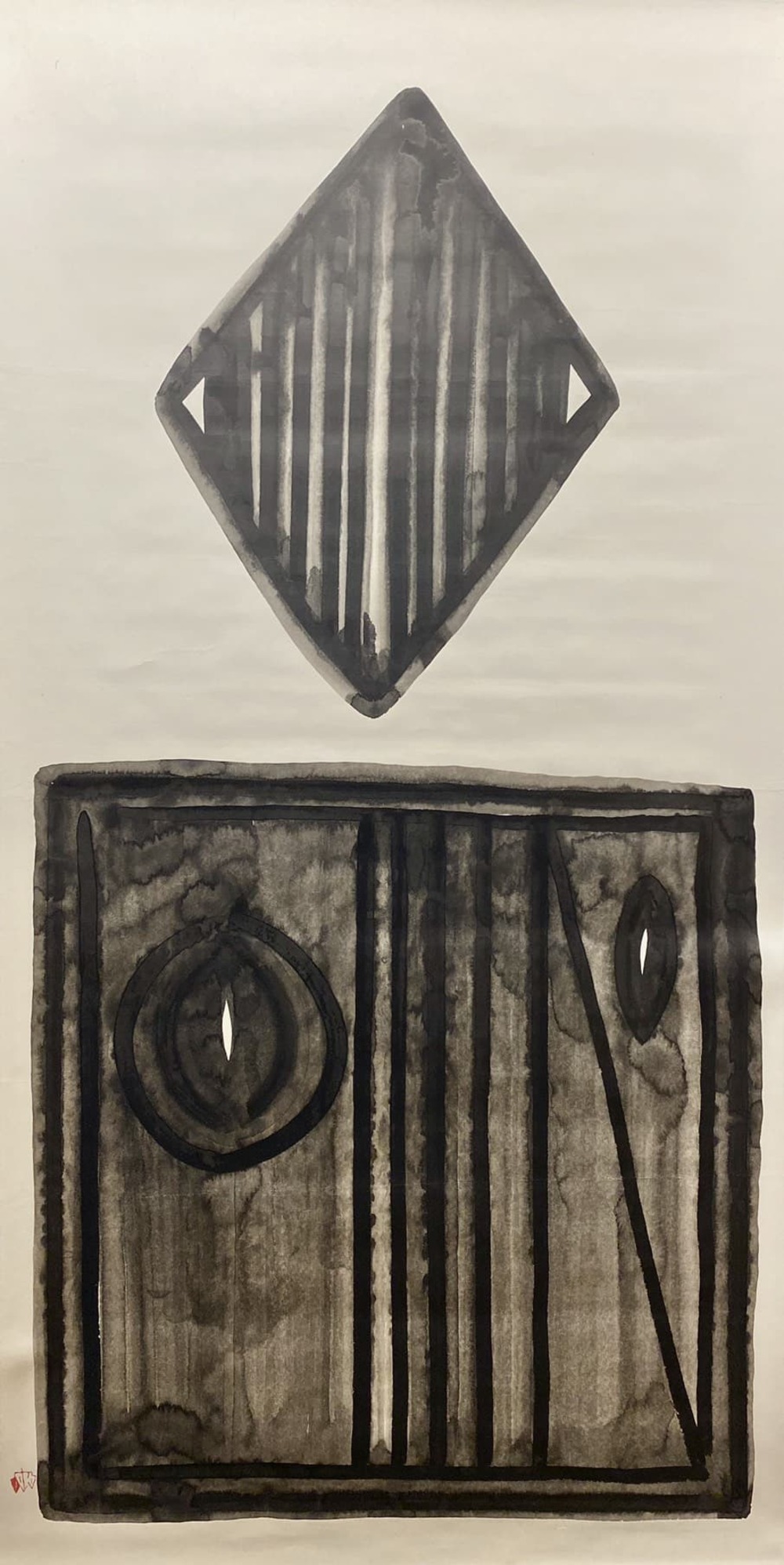

Takeshi Sohu "untitled"

ink on paper

182cm×93cm / 235cm×98cm

Takeshi Sohu "untitled"

ink on paper

96cm×86cm / 193cm×97cm

Takeshi Sohu "untitled"

Hakuin Ekaku "Namu Jigoku Daibosatsu"

ink on paper

135.7cm×28cm / 213cm×39cm

Hakuin Ekaku "Namu Jigoku Daibosatsu"

Hakuin Ekaku "Akihasan Daigongen"

ink on paper

132.5cm×28.5cm / 211cm×41.5cm

Hakuin Ekaku "Daruma"

ink on paper

118.5cm×54.5cm / 217cm×69cm

Hakuin Ekaku "Daruma"

Jiun Onko "Calligraphy"

ink on paper

120.3cm×50.5cm / 182cm×66.5cm

Nisida Kitaro "Calligraphy"

ink on paper

135cm×32cm / 205cm×45.5cm

Suzuki Daisetsu "Calligraphy"

ink on paper, with a box signed and sealed by Seki Bokuo

144.5cm×39.5cm / 222cm×53.5cm

Hisamatsu Shinichi "Kaku"

ink on paper, with a box signed and sealed by the artist

22cm×31.6cm / 107cm×44.5cm

Hisamatsu Shinichi "Kaku"

Hisamatsu Shinichi "Meigetsuya"

ink on paper

22.5cm×31.5cm / 99cm×42cm

Hisamatsu Shinichi "Meigetsuya"

Takeshi Sohu "untitled"

ink on paper

182cm×93cm / 235cm×98cm

Takeshi Sohu "untitled"

ink on paper

96cm×86cm / 193cm×97cm

Takeshi Sohu "untitled"

Shinichi Hisamatsu said that Zen art has seven characteristics: asymmetry, simplicity, austere sublimity, naturalness, profound subtlety, freedom from attachment, and tranquility.

Breaks the symmetry to reach asymmetry, concise, acts like an old pine tree, unintentional innocent look, self-discipline and refined, not particular, and calm and quiet—whether it is calligraphy, paintings, tea ceremony utensils, or architecture, these Zen styles can grab you by the collar.

When I look at calligraphy and paintings, I get drawn to how technically skillful they were created and to their figurative ingenuity. This must be because they are easy to understand as perspectives. As long as calligraphy and art history discussions focus on “shaping”, we, of course, cannot stop looking at things in this manner. On the other hand, it is also true that some things created by people cannot be captured by observing techniques and shapes alone.

As a child, Hakuin saw a hot bath as the Eight Hot Hells and was so terrified by it he cried. This fear of hell gave birth to the religious man Hakuin. The invocation in I Entrust Myself to the Great Bodhisattva of Hell was written during Hakuin’s final years. There were several other hanging scrolls written with these words, all of which were written around the same time. Hakuin, who was so afraid of hell, wrote these words in search of hell in bold, which filled the entire writing space. The somewhat joyous expression goes beyond calligraphy, and the boundary between Hakuin’s calligraphy and Zen painting is blurred. The pale black ink color conveys the traces of Hakuin’s brush strokes to the present day.

A passage in Jiun’s analects, which was written vigorously and swiftly with a brush, and Ryokan’s poem about the alms bowl, which was written slowly in So-gana, both carved in relief their existence that was not affected by anything. Their expressions were the results of their thorough and ongoing efforts to confront their inner selves—unique expressions not seen elsewhere. To add to this, I can feel their presence, particularly in the handwriting.

By the way, the abovementioned Shinichi Hisamatsu wrote Zen and the Fine Arts (Bokubisha) in 1958, Bokubi, a journal dedicated to the study of calligraphy that actively introduced Zen-influenced calligraphy written by people such as Hakuin, Jiun, Ryokan, and Beizan Miwada, started publishing in 1951, Eitaro Yabumoto’s Jiun Sonja Iho was published a little earlier in 1938, Yukihiko Yasuda’s Ryokan (Chikuma Shobo) was published in 1960, and Naotugu Takeuchi and Daisetsu Suzuki’s Hakuin (Chikuma Shobo) was published in 1964. Bokubisha was led by the calligrapher Shiryu Morita.

During this period, Japan was in the midst of a period of rapid economic growth after the Jinmu and Iwato booms, and the post-war recovery was summed up by the 1964 Tokyo Olympics. People worked positively to enjoy the freedom of the democratic era and to seek material satisfaction. In tandem with this, people began to realize that they had a different kind of inner richness that they might otherwise have forsaken.

This re-evaluation of early modern Zen calligraphy in the 1950s and 1960s was supported by philosophers like Daisetsu Suzuki, Kitaro Nishida, and Shinichi Hisamatsu. They who act as the theoretical pillars of the global Zen culture were also very practical—their calligraphy was extraordinary.

Among them, the most sensitive reaction to this movement was seen in a group of calligraphers. Shiryu Morita, through Bokubisha, attempted to actively evaluate Zen art, mainly focusing on calligraphy. Apart from the enlightening role he played in publishing, he also explored new expressions not yet seen in the world of calligraphy, such as Kan, the use of lacquer and pigment on paper. His calligraphy was also known as a form of abstract expressionism; it was art that emphasized his inner world as a counterpart to his publishing work.

It was in the stone garden of Ryoan-ji Temple that the Bokujinkai, in which Shiryu was a part of, was born. Yuichi Inoue was one of the five people who assembled there. I Entrust Myself to the Great Bodhisattva of Hell may have been written based on Hakuin’s works, but the hell of Inoue, who experienced the Bombing of Tokyo, may be different from Hakuin’s—something that is seen on the horizon. It is not often that we can see these two aligned sides by side.

Sofu Takeshi was of the same generation as Shiryu and worked with Gakyu Osawa and Chikutai Osawa. Along with Nankoku Hidai, he was known to have produced many non-literate calligraphy works. It was during this period of Zen calligraphy that he struggled in his attempts to give form to human emotions that cannot be expressed through writing. Alongside Gakyu, who respected the popular humanism that resembled a folk art movement, Sofu continued to struggle to express his unspoken emotions through calligraphy. His vigorous creative desire continued to persist, and until he died in 2008, he never abandoned his tendency for non-literal works.

Hakuin, Jiun, and Ryokan were all prominent figures in history, and it is clear that their calligraphy works have a solemn distinctness that others cannot interfere with. However, we feel a sense of relief that defies logic when we see them in front of us. Shiryu concluded that the book Zen and the Fine Arts would help us to “discover and practice not only fine arts but also the true way of living in all humans”. Perhaps this sense of reassurance had derived from the fact that the true image of a person stripped of his or her affectation is projected onto brush painting.

Text by Toshiro Takahashi of Daito Bunka University

Location

Matsumoto Shoeido Tokyo Store

Nakamoto Bldg. 3F, 3-8-7 Nihonbashi, Chuo-ku, Tokyo 103-0027, JAPAN

Mob:+81-80-9608-7598 (Japanese only)

Mail:info@matsumoto-shoeido.jp

We are open 10:00-18:00